Abstract

We don’t know much about the smells of the past. Yet, odours play an important role in our daily lives: they affect us emotionally, psychologically and physically, and influence the way we engage with history. Can this lead us to consider certain smells as cultural heritage? And if so, what would be the processes for the identification, protection and conservation of those heritage smells? In order to answer these questions, the connection between olfaction and heritage was approached in three ways: (1) through theoretical analysis of the concept and role of olfaction in heritage guidelines, leading to identification of places and practices where smell is fundamental to their identity, (2) through exploration of the evidence for use of smells in heritage as a tool to communicate with audiences; and (3) through experimental evaluation of the techniques and methods for analysing and archiving the smells, therefore enabling their documentation and preservation. We present this through the framework of Significance Assessment—Chemical Analysis—Sensory Analysis—Archiving. The smell of historic paper was chosen as the case study, based on its well-recognized cultural significance and available research. Odour characterization was achieved by collecting visitor descriptions of a historic book extract through a survey, and by conducting a sensory evaluation at a historic library. These were combined with the chemical information on the VOCs sampled from both a historic book and a historic library, to create the Historic Book Odour Wheel, a novel documentation tool representing the first step towards documenting and archiving historic smells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Our knowledge of the past is odourless. Yet, smells play an important role in our daily lives: they affect us emotionally, psychologically and physically, and influence the way we engage with history.

In this work, we propose that smells are part of our cultural heritage, and that a structured approach to researching them is required. Several aspects allow us to explore the connection between olfaction and heritage. We will define heritage smells and argue their importance, by focusing on the following: (1) a theoretical review of olfaction and odours in heritage, including (a) the consideration for smells in heritage documents and guidelines, leading to the identification of smell as part of cultural significance of a place or object and (b) the use of smell in a heritage context as a means to engage and communicate with the audience; and (2) techniques for identifying, analysing and archiving smells and therefore enabling their characterization and preservation. These techniques can be approached from two complementary angles: firstly, the chemical analysis of the source of sensation, in our case chemical analysis of the compounds that lead to perception of the smell. Secondly, sensory characterization of that smell in terms of human perception. In the case of historic smells, this dual approach can contribute to a holistic understanding of what the odour represents in terms of the nature, history and state of the object.

Since this is the first comprehensive scientific treatise of the subject, the introduction deals with the issues of significance and use, as well as characterisation, in the following three subsections.

Olfaction and heritage

The significance of olfaction in the context of cultural heritage, evidencing that smells can be fundamental in shaping who we are, where we belong and how we experience encounters with different cultures, has been recently examined in several case studies. They show that odour can be part of the local identity through history [1]; that a central place for olfactory experiences in a culture results in a much wider vocabulary to discuss smells [2] and that travel and tourism offer an opportunity to approach the world with our noses [3]. However, the role of smells in our perception of and engagement with the past has not been systematically explored.

Odours are powerful triggers for emotions via the limbic system of the brain, which deals with emotions and memory [4, 5]. They are an effective way to evoke recollections; certain aromas can even act as part of the common memory of a generation. For example, people born before 1930 tend to display positive association with nature scents, and the fragrance of Playdough triggers nostalgia in those born after 1960 [6]. Scents can also influence behaviour: in shops, a pleasant scent positively impacts customers’ attitude towards the store, the evaluation of products and intention to revisit the place [7]. A British company claims that treating customers with the smell of male sweat made them 17% more likely to pay their bills than a control group [8]. Mood and cognitive function are also affected: although olfaction is one of the least considered senses in pedagogy, aromas can improve learning through their connections with memory, mood and productivity [9].

In the heritage context, experiencing what the world smelled like in the past enriches our knowledge of it, and, because of the unique relation between odours and memories, allows us to engage with our history in a more emotional way [10]. Odours are also powerful cues to remember an exhibition, as demonstrated by Aggleton and Waskett [11] in their work at the Jorvik Viking museum in York, England. In the case of a gallery, the presence of point-of-scent components heightens the enjoyment of the public, in comparison to experiencing the same displays without smells [12].

Smell as part of cultural significance

There is currently no strategy in the UK for the protection or preservation of smells. In heritage guidelines, odours are often recognized as a value associated with a place, or with certain practices. Currently, smells are viewed as an aspect of cultural significance, an overall measure of the value of a particular place to the public, as introduced by the widely adopted Burra Charter [13]. Aesthetic value contributes to cultural significance and includes ‘aspects of sensory perception for which criteria can and should be stated’, and, as an example, ‘the smells and sounds associated with the place and its use’. In this sense, smell can be considered as an intangible property of tangible heritage and inextricably linked to it.

However, unlike some food and culinary practices, smells are not recognized in the definition of intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. In spite of sharing a relation to other aspects of intangible cultural heritage, such as language, industries, and tourism [14], the olfactory world is hardly discussed or documented.

According to the guidelines published by the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England (formerly English Heritage), the smells of a place are considered of value because they affect our experience of it. For this reason, they should be taken into account when defining the character of a historic area [15].

The connections between odours, locality, and identity are also a component of tourists’ experience. With globalization, we see that a location and the authentic experience of it are not always linked, because it is possible to have an experience that is perceived as authentic far from the original location. For this type of tourist, authenticity lies with the experience (existential authenticity), not with the place [16]. Likewise, it could be said that reproducing historic or heritage smells without their original physical context would be looking to provide an existentially authentic experience.

The link with a place and its identity is not sufficient to encompass all kinds of smells. Odours on their own, such as historic perfumes, are not formally classified as heritage, in the way buildings are by international standards of conservation such as the Venice Charter [17]. This was recognized by Henshaw [18], who studied the way smells defined the urban environment, by conducting guided ‘smellwalks’ around different European cities. She stated: “In the UK, we have something called listed building status, so that beautiful buildings are protected and we’re not allowed to redevelop them. But there aren’t those equivalents for beautiful sounds or beautiful smells”. The temporary nature of odours, as well as the absence of a standardized vocabulary to talk about them, might be contributing factors to this state of affairs.

Specific smells can also be related to cultural practices, expressions and knowledge. As an example, the art of Asian perfumery is threatened by industrialization and may be in need of protection. The smells carry the information about how practices have evolved throughout history, the materials associated with them and the conditions in which smells were experienced [19]. In this case, smells are associated with intangible practices, although they still emanate from a tangible source, as knowledge has no smell.

An example of a community-led selection of aromas recognized as heritage can be found in the Japanese Ministry for the Environment ‘100 most fragrant’ list, which was established in 2001 after a nationwide consultation where 5600 candidate smells were submitted by local groups. The aromas included ancient woods, sea breeze, sake distilleries and a street lined with bookshops. The 100 chosen aromas and their sources are now protected and carry a seal that reads ‘scents to be handed down to our children’. In addition to the recognition of significance as a cultural legacy, these smells are also an important element of regional promotion [20].

This year (2017), UNESCO is considering the application to have the skills, knowledge and practices associated with perfume making in the region of Grasse (France) recognized as intangible heritage [21]. Given that there is no mention of smells among the 38 elements inscribed on the organization’s list between 2009 and 2014, the recognition of the olfactory heritage of Grasse would create an important precedent.

As the place of smell in heritage has begun to be discussed, so has the observation that the dynamic nature of olfactory ‘objects’ does not fit well within the current definition of intangible heritage [1, 19]. This presents a specific set of challenges in current museum practice when smells are used as part of collection interpretation.

However, not every historic smell is a suitable candidate for analysis and preservation, because not all historic smells have heritage value. Therefore, the first step in the proposed framework involves the identification of heritage smells.

Some concepts from the current evaluation policies can be helpful to illustrate how the cultural value of a smell can begin to be considered for its designation as olfactory heritage. Associative characteristics, an important aspect the determination of cultural significance of Scottish historic monuments [22], are considered more subjective than intrinsic or contextual ones. They include ‘significance in the national consciousness or to people who use or have used the monument, or descendants of such people’ and ‘the associations the monument has with historical, traditional or artistic characters or events’. In the context of this work, the associative aspect reflects the relevance of the provenance of a certain smell. It also encapsulates the importance of understanding the role of that smell in the public’s memory or collective imagination.

Out of the four sets of values identified by Historic England, there are two that can be relevant to assess the significance of a smell: historic value, both in its illustrative aspect, which ‘has the power to aid interpretation of the past through making connections with, and providing insights into, past communities and their activities through shared experience of a place’ and its associative aspect: ‘association with a notable family, person, event, or movement gives historical value a particular resonance’. Communal value is also an assessment category that can be used to consider the cultural value of a smell. It derives ‘from the meanings of a place for the people who relate to it, or for whom it figures in their collective experience or memory’ [23]. Finally, interpretive criteria, defined by the Heritage Collections Council of Australia as ‘the value or utility the object has for a museum as a focus for interpretive and educational programs […]’ may also be significant for its links to particular collection themes, histories, or ways of seeing the collection [24].

Smell in the museum

While museums were once spaces where handling objects as a way of exploring them was encouraged, these practices changed in the nineteenth century with the increase of the number of visitors (and potential for damage to collections), and more sophisticated display techniques that allowed seeing objects well without touching them [25].

Visual communication is still dominant in the museum of today. However, all experience of the world is multisensory, whether or not it has been designed as such [26]. The benefits of a multisensory approach to the examination of historic objects and practices have been argued [27, 28] and since the turn of the century many heritage institutions have been staging multisensory exhibits. The inclusion of smell in museums can be related to attracting more visitors, adding a ‘dose of reality’ to the displays, exploring the connections between olfaction and other senses and even claiming a space for perfume as an art form.

In contrast with the mentioned Jorvik museum, where smells illustrate Viking life 1000 years ago, an exhibition in the Reg Vardy gallery in Sunderland in 2008 presented smells without a visible source, just in a white, clean room. Robert Blackson, curator of the show, said the scents were “inspired by absence. Their forms are drawn by the disparate stories throughout history for which few, if any, objects remains” [29]. Among the 13 smells were a bouquet of extinct flowers, communism and the scent of Cleopatra’s hair.

In addition to engaging the visitors to rethink the past as an odorous place, smells in museums can be a way of relating to the world of the ‘other’. In their work on presenting the country’s history in the National Museum of Australia, Wehner and Sear [30] sought to display works to encourage visitors to engage with subjective experiences. For example, one of their sensory stations included ‘the pungent smell of dried sea cucumber’ alongside cooking tools of Trepang fishermen.

Scenting a heritage space poses several curatorial challenges. Drobnick [31] argues that there is a risk that audiences might feel manipulated when the identity of the smell is not clear. The use of synthesized scents in this context, as opposed to ‘authentic’ (as in related to a unique material source) is also questioned by this author. This is partly because, whenever no olfactory artist is signing the work, museums tend to rely on commercial fragrance providers to scent exhibitions. Their catalogues are rich in aromas related to food and daily activities (‘banana’, ‘aftershave’), and interpretation/conceptual ones: ‘burning witch’ is offered as “history lesson in a smell, turns out witches smell a bit like bacon!” (Dale Air, Sensory Scent, 2015).

The issue of authenticity of smells used in heritage spaces leads us to consider the relationship between the olfactory properties of a source and the perception of its smell. A comparison with colour, another intangible property of tangible objects, might be useful. Colour can be described as an attribute of an object, and different theories consider it objective (i.e. depending on the object), subjective (i.e. depending on the viewer), or relational, where colour is a property that involves both physical objects and those who experience them [32]. Smells can be treated in a similar way: as an attribute of the object, independent of the nose which smells it, a perception completely dependent on the smeller, or a communication between source and receptor, where meaning is created. The perception of a smell as authentic is, then, the result of an interpretation process, which we will explore on the basis of a case study.

Characterisation of smells

Since most odours are composed of volatiles organic compounds (VOCs) [33, 34], the analytical methods frequently involve headspace solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS). However, it needs to be stressed that not all compounds that could trigger the sense of smell can be determined using this technique. For inorganic compounds, and some organic compounds that are difficult to sample using SPME, other sampling and analytical techniques may be more useful, from direct detection to various types of separation techniques [35].

SPME was developed in the 1990s by Pawliszyn et al. [36, 37] and is used for extracting volatiles in the headspace over liquid and solid samples. It has been used successfully to extract and analyse VOCs from historic materials [38], including paper [39, 40]. GC–MS techniques are routinely used to analyse perfumes and cosmetic preparations [41].

SPME–GC–MS as used in this paper has been specifically optimized for analysis of the headspace of objects made of organic materials, such as book and paper [33], leather and parchment [42] and has been successfully used to sample air in libraries [43]. Recent research shows that the profiles of volatile organic compounds found in historic libraries can be directly linked to the emissions from decaying books and wood furnishing [43], which makes it reasonable to assume that sampling VOCs both from books and from library environments can be done using the same technique, i.e. SPME-GC–MS.

The vocabulary we use to describe smells is important and it is essential that a methodology to describe odours for archival purposes includes a sensory description, in addition to the chemical one. In some industries, the human nose is the main tool to characterize odours due to its accuracy and sensitivity [44]. Human olfactory experience depends on several factors, including genetic profile, ethnic background, gender, age [45], cultural background [46], and overall physical environment. The person’s mood at the time of sampling can also have an impact on description of the hedonic tone (pleasant/unpleasant) of the smell [10]. Information on the evaluator and the evaluation circumstances can therefore be valuable metadata on the heritage smell.

The terminology to describe heritage smells is not standardized, in line with the general poverty of the olfactory vocabulary [4, 47]. However, this is independent of our ability to perceive and identify different smells, and respond to them [48]. Many attempts have been made to unify the way to describe odours pertaining to flavour, fragrances, or malodours [47, 49, 50]. Working with reports of odour nuisance, Curren [51] developed an odour wheel based on descriptions by the complainants and cross-referenced it with potential odour-causing compounds. Recently, a bilingual (English–Spanish) dictionary for urban smells was created, using information from literature and urban smellwalks, and relating the selected terms to social media tagging [52]. This latest experiment evidenced that, despite challenges posed by the ephemerality and invisibility of smells, techniques such as the ‘nose-led’ walks and crowdsourcing make the documenting of odours possible and even accessible.

All of the aspects considered in the Introduction could serve as a general framework to identify and document smells with historic value: (i) Significance Assessment; (ii) Chemical Analysis; (iii) Sensory Analysis; (iv) Archiving. Along with studies of the human experience of the odour, these aspects benefit the conservation, management and interpretation of cultural heritage, and are thus within the domain of heritage science as set out by the UK’s Institute for Conservation (ICON) in 2006 [53].

This opens up a new field of documentation and archiving (as well as conservation) of historic smells with heritage value, the foundations of which we explore in the frame of a case study based on the well-known and appreciated historic library smell, where we propose the Historic Book Odour Wheel as a key documentation tool.

Results and discussion: the smell of historic paper

Significance assessment

Often, the smell of books intrigues and inspires: a copy of the novel Ulysses which belonged to T. E. Lawrence, and documented as having ‘a sweet, somewhat smoky aroma that suffuses every bit of paper and leather’, embarked several researchers in a quest to find out the author’s life experiences behind the fragrant notes [54]. In this case, association with a prominent author gave significance to the information resulting from the VOC analysis.

Old books smell like ‘a combination of grassy notes with a tang of acids and a hint of vanilla over an underlying mustiness’ [34]. These aromas, along with those of the surrounding furnishings of a historic library space, create the unique smell that many visitors appreciate, conferring significance to this aroma through its communal value. Similarly, users of archives consider smell as an important characteristic of documents; this could be related to the fact that, in the age of digitization, working with physical records is an increasingly rare practice, and therefore the opportunity to touch and smell the documents is perceived as valuable [55].

Visitors to St Paul’s Cathedral Dean and Chapter Library, a eighteenth-century space designed by Christopher Wren, often register their appreciation of the aroma of the space in the guest book: “City guide trainees we all loved the smell and beautiful library” (11/02/15); “Amazing place! I can inhale the knowledge” (09/03/15); “We can smell the history, the fragrance of heritage and our communion with souls of the past” (04/11/15). In this case, in addition to the explicit communal value, the smell becomes culturally significant by its association with a heritage space and its collection.

Further evidence of the significance of the smell of books in the collective olfactory memory is the number of scented products themed on books and libraries (over 30 candles, perfumes and oils) available from a single London store in 2015. As convenient as e-readers may be, many readers long for the nostalgia that the smell of a book can evoke [56].

The case for the smell of books as a case study is strengthened when the cultural significance is coupled with the research conducted on the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) constituting the aroma of historic books as a non-destructive diagnostic tool for paper degradation [34, 57], which the next section will address further.

Chemical analysis

The goal of this experiment was to gain information on VOCs emitted by historic paper and compare it with the VOCs found in the environment of the library in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London (Fig. 1).

A selection of the major VOC peaks found in the historic book and the historic library is presented in Table 1. The criteria for selection was to include those compounds that (1) had been previously observed in naturally aged paper, and correspond to cellulose and lignin degradation products [34], (2) corresponded to volatiles with a smell known to be perceivable by the human nose [58, 59] and 3) had a significant peak area (>300,000 AU), which clearly separated it from possible noise. The results of analysis of the two samples (one from an historic book and one from the environment of a library, details of methodology in “Experimental methodology” section) are presented in a single table since most of the compounds were present in both samples, so they were documented in conjunction. The degradation reactions are either hydrolytic or oxidative and lead to the production of VOCs in varying proportions, depending on the composition of paper and its rate of degradation [34]. The data in this table could be used as a base to potentially recreate the smell in the future and may thus be of archival and conservation value.

As is evident, the smell of historic books is a complex mixture of compounds. However, in order to interpret the chemical information, we need to explore the appropriate terminology and method to describe it.

Sensory analysis

The attribution of odour descriptors to the library environment is a way to contextualize the chemical findings. It can highlight the odorants most easily perceived by the human nose in the sample but also potentially identify smells that were not extracted by the SPME fibre.

In the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, where visitors where presented with the (unlabelled) historic book smell, a total of 120 descriptors were collected from 79 respondents (Additional file 1). A wordcloud (Fig. 2) was generated using text analysis software (Voyant Tools v. 1.0), which presents more frequent terms in a larger font size.

The word ‘chocolate’ was the most recurrent, with 21 mentions [27 if grouped with similar descriptors such as ‘cocoa’ (3), ‘Cadbury’ (2) and ‘chocolatey’ (1)]. It was followed by ‘coffee’ (10 mentions), ‘old’ (8), ‘wood’ (4) and ‘burnt’ (4). There were three descriptors with three mentions each, and eleven descriptors that were mentioned twice.

Since the historic book smell was one of eight odours presented to the visitors during the exercise, it is possible that some of the descriptors for this smell were contaminated through sampling the other aromas, which included ‘chocolate’, ‘coal fire’, ‘old inn’, ‘fish market’, and ‘dirty linen’, coffee and HP sauce. It has been observed that providing linguistic or visual cues prior to odour sampling can affect the olfactory experience and influence smell classification [60]. However, there is also evidence that in non-ambiguous smells (which would be the case of the familiar scents of coffee and chocolate), the misperception triggered by the verbal context does not go beyond smells closely associated with the ones perceived [61].

From the analytical perspective, and given that coffee and chocolate come from fermented/roasted natural lignin and cellulose-containing products, they share many VOCs with decaying paper. Cocoa as well as coffee are known to contain significant amounts of furfural and furanoid compounds, acetic acid, higher aldehydes (heptanal, hexanal, octanal), vanillin and benzoic acid [62, 63] and many other compounds identical to those in decaying paper (Table 1). It would therefore appear to be reasonable to expect for museum visitors to associate the aromas of chocolate and coffee with that of historic paper, considering that many identical volatiles in the aroma profiles of the three substances are identical and that in addition, the same visitors were primed to think of chocolate and coffee while visiting the exhibition prior to responding to the questionnaire.

In addition to describing the smell, people tended to spontaneously comment on hedonic tone and intensity. This information can anchor sensory perception in a time and a place, which is important: the description of a ‘rancid’ smell in a pre-refrigerated age might not necessary compare to what we consider ‘rancid’ today [64].

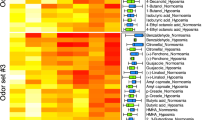

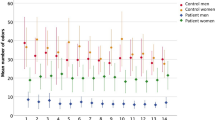

Regarding the sensory evaluation of the library, within the given list, ‘woody’ was the only descriptor of the list selected by 100% of the assessors, followed by ‘smoky’ (86%), ‘earthy’ (71%) and ‘vanilla’ (41%), as shown in Fig. 3. The smell was also described as ‘musty’, “sweet’, ‘almond’ and ‘pungent’ by 29% of the panellists (Additional file 2). Finally, the descriptors ‘medicinal’, “floral”, ‘fruity’, ‘green’, ‘rancid’, ‘bread’, ‘citrus’, ‘sour’ and ‘creamy’ were chosen by 14% of the participants each, whereas ‘chemical’, ‘paint’, ‘fatty’ and ‘minty’, which also corresponded to odorants found in the VOC analysis, were not considered relevant by any of the panellists (Fig. 3). In the ‘other’ descriptor, the participants entered ‘enclosed’, ‘yellowish brown’, ‘historic’, ‘old books’, ‘distinct’, ‘chemical’ and ‘sharp’. As per the visual and verbal cue influence on odour classification, the relation of these findings to the visual cue of the space (since the experiment was conducted in the library, participants could see wooden furniture, old books, etc.) and the verbal context of the given odour descriptors needs to be further explored.

Regarding intensity, the average intensity noted was 4.36, which sits in the scale between ‘strong odour’ (4) and ‘very strong odour’ (5), as shown in Fig. 3.

Finally, the panellists rated their perceived pleasantness or unpleasantness (hedonic tone) of the library odour. On a scale that ranges from −4 (very unpleasant) to +4 (very pleasant), over 70% of the assessors described the smell as ‘pleasant’. 14% rated it as ‘mildly pleasant’ and 14% as ‘neutral’.

Archive tool: historic paper odour wheel

Combining the chemical and sensory analysis of a smell to produce a holistic characterization of it is an effective practice, usually used for edible or perfume samples [65, 66]. Creating an odour wheel for historic smells, where untrained noses could identify an aroma from the description and gain information about the chemical causing the odour, establishes a novel method of heritage documentation.

Odour wheels are created from information provided by a sensory panel on odour character and intensity. They have been developed and used successfully to characterize smells related to drinking water and wastewater [50].

For the historic paper odour wheel (Fig. 4), categories present in Suffet and Rosenfeld’s urban wheel were the starting point. All the descriptors were used in the evaluation. For example, old room, musty and dampness were grouped under the main category Earthy/Musty/Mouldy. When no existing categories from the urban wheel encompassed the descriptions, a new category was created.

With the main categories in the inner circle and the descriptors in the outer circle, the aroma wheel also features the likely chemical compound causing the smell. In this case, the data has been matched using the information provided by the descriptions from the museum’s public, the categories from the urban aroma wheel and the data from the GC–MS analysis of the historic book, referenced by established odour description databases (Table 1).

Odour wheels are dynamic tools: they evolve when new information is gained about the causes of a particular smell [50]. While they tend to be used in sensory panels, there is evidence that trained and untrained assessors identify similar global differences in aroma perception [67]. Therefore, some odour wheels, such as the original wheel for wine tasting designed by Noble in the 1980s, are intended for use of both professional and lay assessors [68]. This historic book odour wheel is intended to be a inter-disciplinary collaboration tool, used by untrained noses to ‘translate’ curatorial or conservational concerns about materials degradation into an understanding of the underlying chemical compounds causing it, and informing conservation decisions. The chemical aspects of paper aroma have been researched to a considerable extent in the past decade. It has been shown that some VOCs can be linked specifically to degradation of cellulose (e.g. furfural) and others specifically to degradation of lignin (e.g. benzaldehyde and vanillin), and that the VOC profile of a certain type of historic paper can be linked to its composition as well as to its state of degradation [34]. While a thorough discussion of the associated degradation chemistry and material characterization is outside the scope of the work discussed here, it is worth pointing out that the perceived smell of a historic book could be of importance in artefact conservation, and has been observed to be used by professionals in paper conservation practice.

Furthermore, it could help the interpretation of historic aromas, contributing to developing a common vocabulary to describe them.

Conclusions

At a time where the first olfaction-related inclusion into the UNESCO intangible heritage list is being considered, the discussion around the cultural significance, analysis and preservation of historic smells is highly relevant.

This work has argued that smells can be considered part of our intangible heritage, and that a definition of heritage smells requires an exploration of the relationships aromas have with other aspects of cultural heritage, such as, local practices and traditions, and language.

Experiments confirmed that SPME–GC–MS is a non-destructive, effective technique to record and study heritage smells of organic origin such as book smell. Chemical analysis, in conjunction with sensory evaluation and the use of techniques such as smellwalks, make it possible to go beyond the ephemeral nature of smells to identify, document and articulate them.

The historic book odour wheel is a new tool that combines the chemical and sensory aspects of the odour experience and can be considered a preliminary piece in an archival method for heritage smells. It has the potential to be used as a diagnostic tool by conservators, informing on the condition of the object through its olfactory profile.

In terms of visitor experience and interpretation, the olfactory experience in museums, both as a communication strategy and as an art form, could contribute to improved learning, to a more personal connection to the exhibits and an increased overall enjoyment. Furthermore, a public discussion is essential to develop olfactory vocabulary and to identify aromas that have cultural meaning and significance.

Although supported by (and in dialogue with) olfactory-related research conducted in many fields, this study extends our knowledge of smells in a new direction. Further research, including a formal interdisciplinary discussion and case studies, are required to build these findings into a body of work that could significantly inform and benefit heritage management, conservation, visitor experience design and heritage policy making.

Experimental methodology

VOC sampling

The sample book (Panait Istrati: Les Chardons du Baragan, Bernard Gasset, Paris, 1928) came from a second-hand bookshop in London. It was placed in a 5-L Tedlar bag (SKC, 232-05A) and left at room temperature for 2 weeks. Then, a DVB/CAR/PDMS SPME fibre (50/30 µm) was introduced through the septum into the bag, and exposed for 60 min (fibres were always preconditioned for 30 min at 250 °C before exposure).

In the library environment, the fibres were placed vertically on an even surface and exposed for 1 h and for 24 h. Two further blank fibres were taken to the environment but not exposed; all were then taken to the lab for analysis.

VOC analysis

The fibres were analysed using a Perkin Elmer Clarus 500 Gas Chromatograph with a Clarus 560D Mass Spectrometer. The temperature gradient consisted of the following steps: at 50 °C hold for 10 min, 10 °C/min ramp to 100 °C, 5 °C/min ramp to 200 °C, 2 °C ramp to 220 °C, hold for 20 min, total run time 60 min. The carrier gas was He at 1 cm3/min. The injector temperature was 250 °C (the fibre was removed after 10 min).

The results were analysed using NIST 05 Mass Spectra Library V2.0 and the identified odorous compounds were later matched with smell descriptors using established databases Flavornet and Perfume and Flavorist [58, 59].

An external standard calibration mixture (MISA group 17 non-halogenated organic mix 2000 mg/mL in methanol) was used to follow the performance of the instrument, using the same fibres with an adsorption time of 20 s and a gradient consisting of an initial temperature of 35 °C for 5 min, 10 °C/min ramp to 200 °C and then hold for 10 min. This method included a 2-min solvent delay. No quantitative calibration was attempted.

Paper extraction

The chosen solvent was methanol (M3641, Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham), which has been proven effective for extracting plant materials [69]. Its toxicity and flammability were considered potential drawbacks; so the samples were only used after methanol was evaporated.

547.45 mg of the paper sample were cut into small pieces and placed in a 1000-mL Duran bottle (previously heated overnight at 100 °C to clean it), fitted with silicone septa. The bottle was heated in a fan-assisted oven (PN30, Carbolite, Hope) at 100 °C for 2 h. The degraded sample was then placed into a 10-mL plastic vial (60.9920.821, Sarstedt, Nümbrecht) with 7 mL of methanol. After stirring using a VWR Analog Vortex mixer for 35 min, the extract was decanted into another vial. 0.5 mL of the solution was transferred to a Chromacol 20-mL glass vial (20CV, Thermo Scientific, Loughborough), with a screwcap and a silicone septum. The extract was sampled using a DVB/CAR/PDMS SPME fibre (50/30 µm) and analysed with the GC–MS method detailed above, with extraction time 60 s.

Odour evaluation

Book extract: Birmingham museum and art gallery

The extract of historic book was presented as a smell to the public as part of the permanent exhibit ‘Birmingham: its people, its history’ (rooms 37–42 of the top floor of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, UK). The experiment was designed to take place during school holidays (July 2015) to ensure a large and diverse number of participants, and was carried out over 3 days. At the end of their visit to the exhibition, respondents encountered a table with museum volunteers, who invited them to sample 8 unidentified smells [which were ‘chocolate’, ‘coal fire’, ‘old inn’, ‘fish market’, and ‘dirty linen’, coffee and HP sauce, sourced, respectively, from Dale Air (first five smells), the local coffee shop and Sainsbury’s supermarket] and to complete a short questionnaire, including a question that prompted them to describe the smell of historic book. This was presented using a piece of sterile gauze (9 × 7 cm, Sterile Absorbent Gauze BP, Boots Pharmaceuticals, Nottingham NG2 3AA, UK) soaked in 5 mL of the book extract, left to evaporate for 1 h due to the potential toxicity of the solvent base, and placed in a metal canister (9 × 5.5 cm, from homesale_estore Xin Zou, Qi Fu Road Baiyun District No.5, Guangzhou, CN, Guangdong, 510405, China) with a metal mesh as a lid. The container was closed and the lid secured to the canister with a small metal screw (not included in the original container) to prevent the visitors from opening it. When the container was closed, the book aroma was detectable by the human nose from around a 7–10 cm distance from top of the canister. The container was labeled with a letter and no indication was given, verbally or visually, about the nature of the smell.

Library environment: Wren Library at St. Paul’s Cathedral

A panel of seven untrained assessors were briefed to abstain from the use of scented products and from eating 30 min prior to the experiment, and to reveal any circumstances that might affect their sense of smell, such as a cold. The protocol also advised rating the perceived strength of the library smell as soon as assessors entered the space, to prevent olfactory adaptation (a decrease in sensitivity after a period of exposure). On the day, the group was asked to enter the space and fill in a brief form with 21 pre-given descriptors of odour quality (referenced from the findings of the chemical analysis of the environment and odour-compound databases) plus a category of ‘other’ that they could complete. Although the effect of verbal cues on odour classification, as described in 2.3, was considered in the design of the experiment, the need for the panellists to use easily understood odour descriptors (as opposed to personal associations), in which they had no training, was prioritized. As part of the evaluation, the assessors were asked to also rate odour intensity and hedonic tone against the scales outlined by German Standard VDI 3882 [70] (Additional files 1, 2).

References

Boswell R. Scents of identity: fragrance as heritage in Zanzibar. J Contemp Afr Stud. 2008;26(3):295–311.

Majid A. Cultural factors shape olfactory language. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(11):629–30.

Pan S, Ryan C. Tourism sense-making: the role of the senses and travel journalism. J Travel Tour Mark. 2009;26(7):625–39. doi:10.1080/10548400903276897.

van Toller S. Olfaction emotion & cognition. Int J Aromather. 1997;8(2):22–7.

Krusemark EA, Novak LR, Gitelman DR, Li W. When the sense of smell meets emotion: anxiety-state-dependent olfactory processing and neural circuitry adaptation. J Neurosci. 2013;33(39):15324–32.

Hirsch A. Nostalgia and odors. Child Environ. 1992;9(1):13.

Doucé L, Janssens W. The presence of a pleasant ambient scent in a fashion store. Environ Behav. 2013;45(2):215–23.

Classen C, Howes D, Synnott A. Aroma: the cultural history of smell. London: Routledge; 1994.

Baines L. A teachers guide to multisensory learning. Improving literacy by engaging the senses. Alexandria: ASCD; 2009.

Herz R, Schankler C, Beland S. Olfaction, emotion and associative learning: effects on motivated behavior. Motiv Emot. 2004;28(4):363–83.

Aggleton JP, Waskett L. The ability of odours to serve as state-dependent cues for real-world memories: can Viking smells aid the recall of Viking experiences? Br J Psychol. 1999;90(Pt 1):1–7.

Bembibre C. Our nose as a time machine. MRres in heritage science at UCL thesis, unpublished. 2015.

The Burra Charter: the Australia ICOMOS charter for places of cultural significance. 1999.

Hyojung C. Fermentation of intangible cultural heritage: interpretation of kimchi in museums. Mus Manag Curatorship. 2013;28(2):209–27.

Jones DM. Understanding place historic area assessments: principles and practice english. Swindon: Heritage Publishing; 2010. Revised 2012.

Vidal González M. Intangible heritage tourism and identity. Tour Manag. 2008;29:807–10.

The Venice charter: international charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites. 1964.

Henshaw V. Urban smellscapes: understanding and designing city smell. New York: Routledge; 2014.

Jung D. Perfumery in Asia—reflections upon the natural, cultural and intangible heritage. Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Library HeiDOK; 2015.

Ministry for the Environment. Kaori landscape 100 election Online, in Japanese. 30/10/01. 2001. http://www.env.go.jp/press/press.php?serial=2941. Accessed: 20 Aug 2015.

UNESCO. Les savoir-faire liés au parfum en Pays de Grasse : la culture de la plante à parfum, la connaissance des matières premières et leur transformation, lart de composer le parfum. 2015. http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/index.php?lg=en&pg=00554. Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

Historic environment Scotland policy statement. Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland. 2016.

Drury P, McPherson A. Conservation principles, policies and guidance. English Heritage. 2008;78:30–4.

Heritage Collections Council. Significance - a guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections. Heritage, 75. 2001. http://doi.org/702.88HER

Bacci F, Pavani F. First hand not first eye knowledge: bodily experience in museums. In: Levant N, Pascual-Leone A, editors. Multisensory museum: cross-disciplinary perspective on touch, sound, smell, memory and space. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield; 2014.

Levant N, Pascual-Leone A, editors. Multisensory museum: cross-disciplinary perspective on touch, sound, smell, memory and space. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield; 2014.

Ouzman S. Seeing is deceiving: rock art and the nonvisual. World Archaeol. 2001;33(2):237–56.

Jenner MSR. Follow your nose? Smell, smelling, and their histories. Am Hist Rev. 2011;116(2):335–51.

Blackson R. If there ever was: a book of extinct and impossible smells. Manchester: Cornerhouse; 2008.

Wehner K, Sear M. Engaging the material world: object knowledge and Australian journeys. In: Dudley SH, editor. Museum materialities: objects, engagements, interpretations. New York: Routledge; 2010.

Drobnick J. The museum as a smellscape. In: Levant N, Pascual-Leone A, editors. Multisensory museum: cross-disciplinary perspective on touch, sound, smell, memory and space. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield; 2014.

Hatfield G. Objectivity and subjectivity revisited: colour as a psychobiological property. In: Colour perception: mind and the physical world. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198505006.003.0006.

Dincer F, Odabasi M, Muezzinoglu A. Chemical characterization of odorous gases at a landfill site by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2006;1122(1–2):222–229. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2006.04.075

Strlič M, Thomas J, Trafela T, Cséfalvayová L, Kralj Cigić I, Kolar J, Cassar M. Material degradomics: on the smell of old books. Anal Chem. 2009;81(20):8617–22.

Patnaik P. Handbook of environmental analysis: chemical pollutants in air, water, soil, and solid wastes. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2010.

Arthur CL, Potter DW, Buchholz KD, Motlagh S, Pawliszyn J. Solid-phase microextraction for the direct analysis of water: theory and practice. LC/GC. 1992;10(9):656–61.

Niri V, Bragg L, Pawliszyn J. Fast analysis of volatile organic compounds and disinfection by-products in drinking water using solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1201(2008):222–7.

Curran K, Možir A, Underhill M, Gibson L, Fearn T, Strlič M. Cross-infection effect of polymers of historic and heritage significance on the degradation of a cellulose reference test material. Polym Degrad Stab. 2014;107:294–306.

Clark A, Calvillo J, Roosa M, Green D, Ganske J. Degradation product emission from historic and modern books by headspace SPME/GC–MS: evaluation of lipid oxidation and cellulose hydrolysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;399(10):3589–600.

Lattuati-Derieux A, Bonnassies-Termes S, Lavédrine B. Characterisation of compounds emitted during natural and artificial ageing of a book. Use of headspace-solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Cult Herit. 2006;7(2):123–33.

Zhu M. Rapid study of fragrance loss from commercial soap after use by solid phase microextraction-GC/MS and olfactory evaluation. Anal Sci. 2006;22(9):1249–51.

Strlič M, Kralj Cigić I, Rabin I, Kolar J, Pihlar B, Cassar M. Autoxidation of lipids in parchment. Polym Degrad Stab. 2009;94:886–90.

Fenech A, Strlič M, Kralj Cigić I, Levart A, Gibson L, de Bruin G, Ntanos K, Kolar J, Cassar M. Volatile aldehydes in libraries and archives. Atmos Environ. 2010;44:2067–73.

Gardner JW, Bartlett PN. A brief history of electronic noses, sensors and actuators. Chemical. 1994;18(1):210–1.

Greenberg MI, Curtis JA, Vearrier D. The perception of odor is not a surrogate marker for chemical exposure: a review of factors influencing human odor perception. Clin Toxicol. 2013;51(2):70–6.

Ayabe-Kanamura S, Saito S, Distel H, Martínez-Gómez M, Hudson R. Differences and similarities in the perception of everyday odors: a Japanese–German cross-cultural study. In: Annals of the New York academy of sciences, vol 855. New York: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 1998.

Harper R, Land DG, Griffiths NM, Bate-Smith E. Odour qualities: a glossary of usage. Br J Psychol. 1968;59(3):31.

Keller Andreas. The scented museum. In: Levant N, Pascual-Leone A, editors. Multisensory museum: cross-disciplinary perspective on touch, sound, smell, memory and space. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield; 2014.

Dravnieks A. Odor quality: semantically generated multidimensional profiles are stable. Science. 1982;218(4574):799–801.

Suffet IH, Rosenfeld P. The anatomy of odour wheels for odours of drinking water, wastewater, compost and the urban environment. Water Sci Technol. 2007;55(5):335–44.

Curren J. Characterization of odor nuisance. Unpublished doctoral thesis at UCLA. 2012.

Quercia D, Schifanella R, Aiello L, Mclean K. Smelly maps: the digital life of urban smellscapes. 2015. arXiv:1505.06851v1 [cs.SI].

Mitchell L, Paul L, Winston L. Science and heritage report with evidence. House of Lords. 2006. http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-archive/lords-s-t-select/heritage/. Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

Oram R, Bishop RL. The sweet smell of provenance. Chron High Educ. 2005;52(6):B18–9.

Beentjes G. Digitizing archives: does the user get the picture? MRres in heritage science at UCL thesis, unpublished. 2013.

Bilton N. An e-book fan, missing the smell of paper and glue. New York: The New York Times; 2012. Accessed 2 Apr 2016.

Strlič M, Cigić IK, Kolar J, de Bruin G, Pihlar B. Non-destructive evaluation of historical paper based on ph estimation from VOC emissions. Sensors. 2007;7:3136–45.

Acree T, Arn H. Flavornet database. Geneva: Datu Inc; 2004. http://www.flavornet.org. Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

Moschiano G. Perfume and flavorist flavor library. http://www.perfumerflavorist.com/flavor/library/. Accessed 18 Aug 2015.

Herz RS. The effect of verbal context on olfactory perception. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2003;132(4):595–606.

Herz RS, Von Clef J. The influence of verbal labeling on the perception of odors: Evidence for olfactory illusions? Perception. 2001;30(3):381–91.

Ducki S, Miralles-Garcia J, Zumbé A, Tornero A, Storey DM. Evaluation of solid-phase micro-extraction coupled to gas chromatography–mass spectrometry for the headspace analysis of volatile compounds in cocoa products. Talanta. 2008;74(5):1166–74.

Risticevic S, Carasek E, Pawliszyn J. Headspace solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatographic–time-of-flight mass spectrometric methodology for geographical origin verification of coffee. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;617(1–2):72–84.

Smith Mark. The smell of battle, the taste of siege: a sensory history of the civil war. Oxford: OUP USA; 2014.

Kraujalytė V, Leitner E, Rimantas Venskutonis P. Chemical and sensory characterisation of aroma of Viburnum opulus fruits by solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography–olfactometry. Food Chem. 2012;132(2):717–23.

Darici M, Cabaroglu T, Ferreira V, Lopez R. Chemical and sensory characterisation of the aroma of Çalkarası rosé wine. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2014;20:340–6.

Veramendi M, Herencia P, Ares G. Perfume odor categorization: to what extent trained assessors and consumers agree? J Sens Stud. 2013;28:76–89.

Capone S, Tufariello M, Siciliano P. Analytical characterisation of Negroamaro red wines by aroma wheels. Food Chem. 2013;141:2906–15.

Eloff NJ. Which extractant should be used for the screening and isolation of antimicrobial components from plants? J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;60:1–8.

Beuth Verlag, VDI 3882:1997. Part 2: Olfactometry—determination of hedonic odour tone. Dusseldorf, Germany.

Authors’ contributions

CB and MS jointly developed the concept of this research. CB surveyed the literature, modified the research methodology and collected the data, and developed the concept of the historic odour wheel. Both co-authors interpreted the data and contributed to the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Smell of Heritage project supervisors Susanne Kuechler (UCL), Siobhan Barratt (National Trust) and Ton van Harreveld (Odournet), as well as Deborah Cane and colleagues (The Birmingham Museum Trust), Jo Wisdom (librarian at the St Paul’s Cathedral Dean and Chapter Library), and Katherine Curran and Mark Underhill (UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage), as well as the library volunteers for their help with this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Funding by the UK EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Science and Engineering in Art, Heritage and Archaeology and by the National Trust is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bembibre, C., Strlič, M. Smell of heritage: a framework for the identification, analysis and archival of historic odours. Herit Sci 5, 2 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-016-0114-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-016-0114-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Visitor’s experience evaluation of applied projection mapping technology at cultural heritage and tourism sites: the case of China Tangcheng

Heritage Science (2023)

-

Assessment of volatile emissions by aging books

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Evaluating volatile organic compounds from Chinese traditional handmade paper by SPME-GC/MS

Heritage Science (2021)

-

Does Archaeology Stink? Detecting Smell in the Past Using Headspace Sampling Techniques

International Journal of Historical Archaeology (2021)

-

Quantification of formic acid and acetic acid emissions from heritage collections under indoor room conditions. Part I: laboratory and field measurements

Heritage Science (2020)