Abstract

Urbanization has led to homogenizing heritage site landscapes, and the protective measures have become disconnected from public needs. Additionally, the complex and diverse overall characteristics of heritage sites and the uneven distribution of values across different areas are related to the lack of landscape experience assessment. The “subjective + objective” cognitive evaluation and visual perception framework that adopts the Scenic Beauty Estimation Procedure-Semantic Differential (SBE–SD) method and eye-tracking analysis can compensate for the limitations of a single evaluation method by integrating quantitative and qualitative analysis. This research takes the Yi’an Fortress in Zhangpu County, Fujian Province, as the object and examines the visual experiences of different areas and types of landscapes within the Yi’an Fortress. The findings reveal several key insights: (1) Significant differences were found in the landscape experiences of different areas within the heritage site. The visual experience score of the core building area of Yi’an Fortress is (1.01) > the heritage entrance area (0.897) > the residential area (0.841) > the natural ecological area (0.784), indicating that the natural ecological area should be the focus of future protection and development efforts, with a particular emphasis on enhancing the ‘landscape aesthetic’ and ‘landscape cultural’ aspects. (2) The landscape experience scores can be used to understand the reasons for the differences in participants’ experiences of different landscapes. The architectural heritage landscape of the Yi’an Fortress scored highest in the experience evaluation due to its superior performance in terms of ‘landscape form’ factors. The cultural decorative landscape scored next, while the garden greening landscape scored the lowest, due to their poorer performance in terms of ‘landscape form’ and ‘landscape aesthetics’. (3) The eye-tracking data was consistent with the results of the subjective evaluation, validating the “subjective + objective” cognitive evaluation and visual perception framework, employing the SBE–SD method and eye-tracking analysis is a scientific and effective method for assessing the visual experience of heritage landscapes. These results provide a scientific basis for the heritage planners and managers of the Yi’an fortress to improve the landscape environment, better meet public needs, and preserve the unique character of this vital cultural resource. Furthermore, this study offers a new research method and approach for the protection of other heritage landscapes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One such form of a traditional village is the fortress, which is a type of village formed by residents engaging in various production and living activities to adapt to the most basic living conditions [1]. After a prolonged development, the fortress has become a heritage site that preserves rich historical and cultural heritage, ultimately evolving into a heritage landscape through the interaction of regional culture and nature, nurturing a diverse array of landscape typologies. In this context, culture is the driving force, while nature is the medium [2]. Under the influence of post-productivism, traditional agriculture has declined, but the landscape of fortress heritage has attracted significant attention for showcasing local aesthetics and culture. Consequently, increased heritage sites are developing tourism to stimulate regional economic growth. In 2019, the International Council on Archaeological Sites (ICOMOS) held a seminar on “Village Heritage: Landscape and Beyond” in Morocco, and UNESCO has also included it in the Convention for the Protection of the World Natural and Cultural Heritage [3]. However, in the past century, the rapid development of industrialization and urbanization, the widespread implementation of rural revitalization strategies, and the introduction of modern urban construction concepts, processes, and technologies into villages have significantly impacted the heritage landscape of fortresses. This has led to landscape homogenization, such as different perceptions or attention levels of viewers to the landscape [4, 5], interference from chaotic commercial landscapes [6], the landscape experience is poor in villages [7], and new buildings threaten the visual integrity of heritage [8]. These issues are mainly due to the lack of scientific evaluation and analysis of the landscape characteristics of the fortress heritage.

Landscape evaluation is mainly based on the subjective cognition of the viewer towards the value of the landscape, and based on this, makes value judgments. The evaluation method usually adopts methods such as fuzzy judgment theory [9] and analytic hierarchy process [10] to establish an evaluation system around the landscape. However, most evaluation systems originate from urban landscapes, and evaluation methods are often goal-oriented. Previously, heritage landscape evaluation focused more on its aesthetic quality, treating the landscape as an aesthetic entity. Such as the Scenic Beauty Estimation Procedure (SBE) [11], the Law of Comparative Judgment (LCJ) [12], and the Semantic Differential Method (SD) [13]. Yu Kongjian proposed a Balance Incomplete Block-Laws of Comparative Judgment (BIB-LCJ) by combining SBE and LCJ [14]. These methods have been widely used in landscape evaluation research, such as the landscape evaluation survey of Beijing Nature Reserve [15] and the aesthetic evaluation of Zijin Mountain scenic forest [16], including the intervention of Geographical Information System (GIS) and Remote Sensing (RS) technologies, such as the combination of GIS and SBE to construct a park evaluation system [17]. However, the above landscape evaluation methods have not yet freed themselves from subjectivity.

With the continuous deepening of research and the constant innovation and iteration of auxiliary technologies for human behavior research, researchers have begun to use methods such as eye movement, EEG, and MRI to study people’s psychological activities in information processing. Vision is the primary way for people to obtain information [18]. Eye movement analysis can be used to understand the preferences of viewers towards landscapes [19,20,21,22], as well as the differences in landscape perception among different viewers [23,24,25,26,27,28]. These experimental studies often combine subjective perceptual judgments with objective eye movement data to construct visual quality evaluation models. The research results can improve the credibility of landscape evaluation and provide a basis for landscape protection and design management. Research has shown that using eye movement analysis to evaluate landscape visual quality is feasible. Still, there is a limited number of related studies, mainly focusing on landscape visual quality evaluation, landscape preference, and landscape restorative studies based on eye movement analysis. The research objects are mostly forests, nature reserves, waterfront landscapes, etc., with abundant natural resources. More research is needed on the visual quality evaluation of cultural heritage landscapes in fortresses.

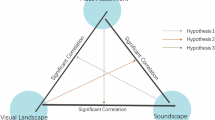

Heritage landscapes are distinct from urban landscapes, reflecting rich historical, cultural, and ecological values. Therefore, the focus should not solely be on the visual impression of heritage landscapes but also the rich spiritual experiences provided by the underlying regional culture, such as a sense of history, Strangeness, Folklore, etc. The heritage landscape is complex and diverse in its overall characteristics, and the values of different regions are uneven. Conducting visual assessments by dividing the area into regions and types can ensure comprehensive identification and protection of the unique values of each region. However, previous assessments have tended to rely on subjective evaluation methods, needing more support from objective experimental data, which limits their scientific rigor. The content of these assessments has focused more on the cultural value, resource status, and physical characteristics of the heritage, neglecting the subjective perceptions of the public. To compensate for this deficiency, this study proposes a new method that combines the SBE–SD method and eye tracking, using a combination of subjective and objective approaches. The subjective experience evaluation integrates the SBE and SD methods. The SBE–SD approach can systematically assess the semantic dimensions behind people’s landscape experiences, including historical, aesthetic, and cultural aspects, to understand viewers’ preferences and rationales for their landscape experiences. On the other hand, eye movement analysis provides insights into the visual attention and cognitive processes involved in landscape perception, obtaining objective data on landscape perception and complementing the limitations of subjective experience evaluation. The research results can provide suggestions for improving the visual experience quality of the Yi’an fortress heritage landscape, providing information for more effective protection and planning strategies to meet the needs and preferences of the public, and better support the sustainable management of heritage landscapes.

Research scope and data sources

Overview of the study area

Yi’an fortress is situated in Zhangpu County, Fujian Province. It was first built in the 26th year of the Kangxi reign (1687) and was donated by Huang Xingzhen, who had previously served as the Inspector of Guangxi, the Governor of Hunan, and the Taichang Temple Minister. It has been built for over 300 years [29] (Fig. 1). Zhangpu County is located at the junction of mountains and seas. In ancient times, people built fortresses and gathered in coastal areas to defend against pirates and bandits. Zhangpu used to have over 50 fortresses, many of which are now abandoned. As a civilian-military fortress, Yi’an fortress is the most well-preserved fortress-type heritage, with significant historical value and local characteristics. In July 2001, it was listed as the fifth batch of national key cultural relics protection units.

Yi’an fortress retains the fortress pattern of the early Kangxi period. The layout of the fortress is in a locked shape, with a clear central axis, and the layout of streets, alleys, and public buildings are well preserved. The city wall is constructed of stone strips, with a circumference of 1200 m, a width of 2.2 m, and a height of 6.7 m. The raceway is 3.3 m wide, with four city gates, each with a width and depth of 4 m. The fortress is mainly composed of residential buildings, equipped with ancestral halls, temples, and other sacrificial buildings. There are currently 127 residential buildings, of which residents inhabit 82. In recent years, the local government has actively promoted the development of tourism based on the protection of historical heritage and explored the potential value of historical heritage.

Research framework

The research framework is shown in Fig. 2.

Main research content

-

1.

The experiential differences of heritage landscapes in distinct regions of Yi’an fortress.

-

2.

The experiential differences of diverse heritage landscape types within Yi’an fortress.

-

3.

The applicability of a novel methodology combining the SBE–SD approach and eye-tracking techniques to evaluate heritage landscape experiences.

Research methodology

Subjects

This study involved 44 Subjects, with 40 valid data obtained. Research has found that when the number of subjects exceeds 24, their gaze patterns when viewing images often become more similar [30]. The SD method typically requires as many samples as possible, but in practical implementation, it is generally controlled between 20 and 50 people [31]. The subjects had normal vision, no color blindness or color vision disorders, and could recognize the landscape types in the photographs. The participants are mostly high school students and include a small number of teachers. The Subjects were college students with some tourism experience and landscape aesthetic judgment abilities, and their aesthetic preferences were consistent with the public’s. Choosing college students as the subjects is feasible and representative [32,33,34], including 18 males (45%) and 22 females (55%), aged 18–34 years (average 25.5 years old), with diverse professional backgrounds. The subjects’ academic backgrounds include history, architecture, geography, landscape architecture, oceanography, computer science, chemistry, psychology, and management, among others, to ensure that the test population encompasses a wide range of preferences.

Determine the tested material

The principles of heritage landscape classification include spatial differences, functional correlations, dominant factors, scale principles, and practicality [35]. Yi’an fortress is a well-preserved historical heritage, with a landscape that combines nature and culture. Based on the heritage value and previous research [36,37,38], Yi’an fortress is divided into four zones: the natural ecological zone (Zone I), the heritage entrance zone (Zone II), the core building zone (Zone III), and the residential living zone (Zone IV) (Fig. 3). The landscape types are categorized into three main groups: the architectural heritage landscape, the cultural decoration landscape, and the garden greening landscape. The architectural heritage landscape refers to the complex physical substance formed by the interplay between buildings, streets, alleys, and the surrounding environment. The cultural decoration landscape encompasses the material expressions of cultural imagery, including cultural buildings such as flagpoles and memorial arches, art forms like couplets, sculptures, doors, and windows, and cultural activities like festivals. The garden greening landscape comprises basic natural elements such as mountains, plants, lakes, and small-scale production activities.

Through communication with the research team, faculty, and students, and based on the fundamental principle of being able to comprehensively and accurately reflect the characteristics of the Yi’an fortress heritage landscape, 40 on-site photographs covering the three landscape types were selected from the various images collected in different regions as the experimental materials (Table 1).

Experimental procedure

In this study, we selected actual photographs of the Yi’an fortress as the eye-tracking experimental materials. Research has shown that photo-based evaluation results are highly consistent with on-site evaluation results [39,40,41]. The photographs were captured starting from the main tourist route of Yi’an fortress, and efforts were made to avoid including non-landscape factors, such as tourists or vehicles, as much as possible. The 40 on-site photographs were taken on June 9, 2023, between 12:00 pm and 5:00 pm using a Nikon D610 camera at an eye level (approximately 1.60 m above the ground), maintaining a 3:2 aspect ratio. To ensure the representativeness of the selected photographs, multiple photos containing rich landscape features were taken during the site visit, and the most representative landscapes were determined through consultations with tourists, managers, and residents to ensure landscape diversity. Landscape evaluation can often be influenced by weather and seasonal conditions [42]. The eye movement experiments were conducted in the college’s eye tracking laboratory, reducing external factors such as light and weather interference and ensuring that subjects participated under consistent experimental conditions to maintain the reliability of data acquisition. In addition to the computer with the eye-tracking device, a separate laptop was prepared for the subjects to view the landscape images. Subjects were guided to sit approximately 50 cm in front of the eye-tracking device screen, and the experimental purpose, process, and requirements were explained to them. Subjects were then asked to complete a basic questionnaire that included age, gender, place of residence, and academic background. After the subjects stabilized, eye-tracking calibration was performed. Following calibration, two warm-up images were displayed without the subjects’ knowledge, after which the 40 experimental photos were shown. The eye-tracking device began recording eye movement data as soon as the image playback started and continued until the entire sequence was completed. Each image was displayed for 8 s, with a 2-s black screen interval for visual focus adjustment. Related studies have shown that the presentation time of most eye movement experiment images is typically 7–20 s, ensuring that Subjects have sufficient time to view the photographs without producing ineffective fixation or eye movement data due to excessive time [43].

After the experiment, the subjects were taken to a well-lit room to complete a subjective evaluation questionnaire. Subjects rated the landscapes in the order of image presentation. The Yi’an fortress heritage landscape has beautiful visual aesthetics and contains profound cultural connotations, so it was necessary to obtain the Subjects’ perceptions of both the visual and spiritual experience aspects. Although eye-tracking indicators and subjective evaluation preferences for heritage landscapes are independent systems, they have a certain degree of mutual influence and constraint [44]. The SBE and SD methods were combined to quantitatively analyze the visual environment and spiritual experience of the Yi’an fortress heritage landscape. The SBE method is a commonly used approach in the psychophysical school to evaluate landscape resources. During the evaluation process, the overall landscape is rated based on the subjects’ visual perception and evaluation criteria [45, 46]. The SD method uses a language scale to measure people’s intuitive perception psychologically, thereby constructing a quantitative analysis of spiritual experience [31].

In this experiment, the SBE method adopted a 7-point scale, with 1 point being “very disliked” and 7 points being “very liked”. The SD method generally utilizes 5–7 evaluation scales [47]. Considering the accuracy and difficulty of the evaluation, the scale in this study was set to 5 segments, with scores ranging from − 2 to 2, where the lower the score, the closer it is to the left adjective. Based on the characteristics of the Yi’an fortress heritage landscape and related research [7, 48], 20 pairs of adjectives were established, including Naturality (N), Diversity (D), Cleanliness (C), Strangeness (S), Orderliness (O), Vividness (V), Culture (Cu), Agreeableness (A), Artistry (Ar), Artistic Conception (AC), Belongingness (B), History (H), Rustic (R), Coordination (Co), Appreciation (AP), Spatial Scale (SS), Aesthetic Perception (AP), Attraction (AT), Folklore (F), and Exquisite (E).

Data collection

This study utilized the Tobii Glasses 2 eye tracking device to record the eye movements of the subjects in binocular pupil mode, with a sampling rate of 100 Hz. The data was collected and analyzed using the Tobii Pro Lab software. This study selected six eye movement indicators: total fixation duration (TFD), first fixation duration (FFD), average fixation duration (AFD), fixation count (FC), average saccade amplitude (ASA), and saccade count (SC). The specific meanings and definitions of these indicators are provided in Table 2. After the experiment, Subjects were required to complete an SBE–SD questionnaire. The questionnaire data was then collected, inputted into an Excel spreadsheet for organization and classification, and prepared for the subsequent correlation analysis with the eye-tracking data.

Data analysis

After the experiment, six eye movement indicators related to the landscape characteristics of the Yi’an fortress were extracted, and the collected data was visualized. A total of 44 data were collected, of which 4 were considered invalid due to a sampling rate below 80%, leaving 40 valid data. The completed SBE–SD questionnaire data was then imported into SPSS 17.0 for statistical analysis to determine the heritage landscape experience of the Subjects.

Results

Differences in eye movement indicators in the visual experience of heritage landscapes

The visual indicators may vary depending on the amount of information contained in the image [49]. According to the analysis of the eye movement heatmaps of the 40 valid samples (Fig. 4), the following observations can be made: In Zone I, the TFD is low, while the AFD is high, indicating that the landscape images in this area have relatively less information, fewer features, and low recognition, resulting in the Subjects’ attention being more dispersed. The low TFD and high SC in Zone II suggest that the landscape images in this area have limited information, average features, and high recognition, which can attract the subjects’ attention. Zone III exhibits a low AFD but high TFD, ASA, FFD, and SC, implying that the landscape images in this area have a large amount of information, rich features, and high recognition, which are highly attractive to the Subjects. In Zone IV, the low TFD and ASA, coupled with a high AFD, suggest that the landscape images in this area have less information, fewer rich features, and average recognition, which is less conducive to increasing the attractiveness to the subjects. In summary, the landscape characteristics of the different regions have varying impacts on the concentration and attractiveness of the Subjects.

Landscape features can significantly affect human behavior and eye movement patterns [32, 50]. Using SPSS 17.0 software to analyze the six eye movement indicators (Table 3), the results showed statistically significant differences in total fixation duration (TFD), average fixation duration (AFD), and saccade count (SC). Therefore, further comparisons were made to examine the differences in these three eye movement indicators among the different types of landscapes. The total fixation duration and saccade count for the architectural heritage landscapes are high, indicating that these images contain abundant information and rich features, which makes the Subjects more engaged and interested.

The total fixation duration and average fixation duration are relatively high for the cultural decoration landscapes. At the same time, the saccade count is low, suggesting that these images have a large amount of information but lack rich features, resulting in more limited appeal. In contrast, the garden greening landscapes have relatively low information content, lacking distinctive characteristics and complexity, which leads to the subjects paying less attention to these types of landscapes.

Differences in hotspots of attention in heritage landscapes

Eye movement indicators are closely related to environmental characteristics and visual stimuli [51]. Eye tracking data can reflect the differences in perception of images among subjects but cannot directly identify the most attractive landscape elements. Fixation heatmap, as a simple and intuitive analysis method, can help identify which parts of the landscape elements are more likely to attract the subjects’ attention [52,53,54]. This study used Tobii Pro Lab software to statistically analyze the fixation coordinates and generate fixation heatmaps (Fig. 5), visually displaying the subjects’ areas of interest.

The results show that the fixation points of the architectural heritage landscape are concentrated on the key elements, such as the walls and roofs of the main buildings. The fixation points of the cultural decorative landscape focus on landscape elements with distinct cultural symbols, such as stone roads, flagpole bases, city gates, and city walls. In contrast, the fixation points of the garden greening landscape are relatively scattered, with a broader visual range, and the subjects focus on natural landscape elements such as mountains, ancient trees, water bodies, roads, and the intersection of embankments.

The different landscape types’ visual characteristics can affect the Subjects’ perceptual preferences [55]. The main elements of the architectural heritage and cultural decoration landscapes are in the center of the images, with regular shapes that attract more attention from the Subjects. In contrast, the elements of the garden greening landscape are scattered, with irregular shapes and similar colors, resulting in lower attention. Overall, the subjects showed higher interest in the architectural heritage and cultural decoration landscapes, while the attractiveness of the garden greening landscape still needs to be improved further. These findings provide a basis for the planning, design, and management of heritage landscapes, and attention should be paid to highlighting the visual characteristics of the landscape elements to enhance their attractiveness and meet the perceptual preferences of different types of subjects.

Objective evaluation based on the SBE–SD method

Multiple evaluation methods can comprehensively analyze user behavior and cognitive processes [53, 56]. Eye-tracking data alone can capture users’ gaze patterns, but it cannot clearly explain the underlying reasons for the differences in the subjects’ experiences [57]. Therefore, combining eye-tracking data with other subjective evaluation data can compensate for the limitations of using eye-tracking experiment methods alone and better explain the cognitive activities and experiences of the participants. This multi-dimensional evaluation can provide more prosperous and more reliable data support.

Analyzing the landscape experience in the different heritage zones based on the SBE–SD questionnaire, the SBE scores for the natural ecological area (Zone I), heritage entrance area (Zone II), core building area (Zone III), and residential area (Zone IV) ranged from 3.5 to 5, indicating that the Subjects had a generally positive overall evaluation of the Yi’an fortress heritage landscape. The core building area (Zone III) scored highest, while the natural ecological area (Zone I) scored lowest. Specifically, the Subjects had the most favorable viewing experience in the core building area, while the natural ecological area provided a poorer experience (Fig. 6). Further analysis of the differences using the SD method revealed that the landscape in Zone III had positive ratings regarding history, appreciation, and exquisiteness, resulting in an overall satisfactory viewing experience. In contrast, the landscape in Zone I was rated positively for its naturalistic qualities and spatial scale but was perceived as lacking in exquisiteness, leading to a less favorable viewing experience (Fig. 7).

Analyzing the experiences of the different landscape types based on the SBE–SD questionnaire, the SBE statistics showed that the Subjects preferred the architectural heritage landscapes the most, followed by the cultural decoration landscapes and the garden greening landscapes (Fig. 8). The SD statistics showed the architectural heritage landscapes were rated highly for their Strangeness, Culture, and Attraction. The cultural decoration landscapes scored relatively high in the artistic and aesthetic aspects, but their coordination with the surrounding environment was perceived as insufficient. The landscape greening areas had relatively low ratings across most attributes, except for a high score in Naturality. Their Appreciation and Artistry were also considered insufficient (Fig. 9). In summary, the distinct characteristics of the different landscape types, such as their uniqueness, cultural atmosphere, and artistry, lead to the observed differences in the subjects’ interests and viewing experiences. The eye movement analysis provides insights into the focus of attention, while the SBE–SD evaluation offers explanations for the underlying preferences and perceptions of the Subjects.

Using SPSS 17.0 to analyze the correlation between the SBE values and the landscape evaluation factors (Table 4), it was found that there is a significant correlation (p < 0.05) between beauty and the following factors: naturality, diversity, cleanliness, strangeness, orderliness, cultural significance, agreeableness, artistry, artistic conception, belongingness, rustic, appreciation, spatial scale, aesthetic perception, attraction, and exquisite. However, vividness, history, coordination, and folklore were not significantly related to the perceived beauty of the scenery.

Therefore, it is necessary to explain landscape experience by combining evaluation factors. Using principal component analysis and variance maximization orthogonal rotation method to analyze evaluation factors, KMO = 0.804 and sig = 0.000, indicate a correlation between the variables, which is suitable for factor analysis. Three common factors were extracted with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first common factor (F1) can explain 34.252% of the landscape visual evaluations, the second common factor (F2) can explain 28.512%, and the third common factor (F3) can explain 19.201%. These three common factors can collectively explain 81.965% of the total image information, therefore, can replace the original landscape evaluation factors to explain landscape experience evaluation. The first common factor (F1) includes attraction, strangeness, coordination, appreciation, orderness, rustic, and spatial scale, and is termed the “landscape form” factor. The second common factor (F2) includes naturality, folklore, belongingness, culture, agreeableness, exquisite, and history, and is termed the “landscape cultural” factor. The third factor (F3) includes cleanliness, artistic conception, artistry, aesthetic perception, vividness, and diversity and is termed the “landscape aesthetics” factor. Normalize the variance contribution rate of factor analysis and use it as a weight to obtain the visual experience evaluation comprehensive score \({F}_{n}=0.43{F}_{1}+{0.39F}_{2}+{0.18F}_{3}\) for each image. These data provide a detailed quantitative analysis of the performance of various regional landscapes and types of landscapes in visual experience evaluation.

Comparing the comprehensive Experience Evaluation score (\({F}_{n}\)) with the landscapes of different regions and types in Yi’an fortress (Table 5). The highest experience score (1.01) was found in the core building area, as subjects believed that the ‘landscape form’ and ‘landscape cultural’ presentations in this area were high quality. The second highest scores were in the heritage entrance area (0.897) and the residential living area (0.841). In contrast, the natural ecological area had the lowest experience score (0.784) because subjects perceived insufficient expression of ‘landscape culture’ and ‘landscape aesthetic’ in this zone.

From the perspective of landscape types, the architectural heritage landscape scored the highest (0.929), followed by the cultural decoration landscape (0.904), and the Garden Greening Landscape scored the lowest (0.843). Specifically, at the level of the ‘landscape form’ factors, the architectural heritage landscape had the highest experience score, while the Garden Greening Landscape scored the lowest. At the ‘landscape cultural’ factor level, the cultural decoration landscape scored the highest, while the Garden Greening Landscape scored the lowest. Regarding the ‘landscape aesthetic’ factors, the architectural heritage landscape again scored the highest, while the Garden Greening Landscape scored the lowest.

These findings suggest that the landscape characteristics, including the form, cultural elements, and aesthetic qualities, significantly impact the subjects’ overall experience evaluation and preferences in the different zones and landscape types within the Yi’an fortress heritage site.

Discussion

Differences in subjects’ visual attention to different fortress landscapes

The research results indicate significant differences in visual experience among different types of heritage landscapes in the Yi’an fortress. Research on the World Cultural Heritage site of Hong village, Anhui province has shown that landscapes dominated by natural elements are more attractive [58]. Similarly, a study of Yellowstone National Park in the United States found that tourists generally express high satisfaction and emotional pleasure in their experience of natural landscapes [59]. In contrast, architectural heritage landscapes have been rated lower regarding visual appeal and emotional pleasure [60]. However, research on the Yi’an fortress has found that, compared to cultural decoration and garden greening landscapes, architectural heritage landscapes are more favored by viewers and demonstrate stronger visual appeal. This difference can be attributed to the incomplete protection and development of the Yi’an fortress, resulting in cultural decoration and garden greening landscapes not fully reflecting its rich historical heritage value and characteristics. Specifically, the unique regional architectural forms and detailed features of architectural heritage landscapes such as Xiaozong Ancestral Hall, Dressing Tower, and Wu Temple have aroused strong visual interest among viewers, reflected in the increase in total gaze time and saccade count. These architectural heritages not only have beautiful shapes but also contain rich historical and cultural connotations, which can fully meet the needs of viewers for visual stimulation and spiritual experience. In contrast, cultural decorative landscapes such as flagpole foundations, city gates, and stone carvings at the entrance have attracted some attention from viewers. Still, they are mainly reflected in the longer average gaze time, indicating that viewers pay more attention to interpreting their cultural connotations and relatively less attention to the landscape form itself. This type of landscape reflects the local area’s unique cultural characteristics, meeting viewers’ needs for cultural learning and cognition. The garden greening landscape of Yi’an fortress is mostly strip-shaped green plants along the road, with a single type of vegetation and a monotonous landscape form. Therefore, the total fixation time and eye jumps are relatively low, and the average fixation time is relatively high. This indicates that although garden landscapes provide leisure and relaxation space for viewers, they fail to meet their needs for visual stimulation and environmental beauty fully. Good natural landscapes can often stimulate positive emotions in subjects, such as pleasure and relaxation [61].

From a cognitive experience perspective, architectural heritage landscapes provide rich cognitive experiences for participants through their unique architectural style and historical background. Cultural decorative landscapes provide participants with a profound cognitive experience through their artistic expression and cultural connotations. The garden greening landscape provides rich ecological and environmental education opportunities for participants through its plant configuration and ecosystem. In the future, when protecting and utilizing historical and cultural heritage, the characteristics of different types of landscapes should be fully considered, and targeted planning and design measures should be taken, including enhancing navigation services, interactive experiences, environmental monitoring, art education, digital display, integration of multiple types of landscapes, and ecological education. The viewing experience should be optimized to enhance the comprehensive attractiveness of historical and cultural landscapes.

Differences and similarities in the attraction characteristics of fortress landscape elements

Considering the need to verify eye movement experiments, many scholars have combined subjective evaluation and eye movement analysis to construct evaluation models and conduct research on landscape visual quality evaluation and perception among different populations, all of which have achieved good experimental results. However, this study uniquely combines the SBE with the SD method to quantify the viewer’s experience and explain their perception. The eye-tracking data primarily indicates the level of attention and information acquisition process of the viewer. Still, the use of eye-tracking analysis alone cannot fully explain the viewer’s perceptual experience. Therefore, a correlation analysis was conducted between the experience evaluation and the eye-tracking indicators, and it was found that at the 0.05 significance level, there was a significant correlation between the experience evaluation and the eye-tracking indicators (Table 6).

The eye-tracking results of this study found that the attraction of the core building area of the Yi’an Fortress historical heritage site to the Subjects was higher than that of the heritage entrance area, residential living area, and natural ecological area. The natural ecological area had the lowest attraction. Regarding landscape types, the attractiveness of the architectural heritage landscapes was higher than that of the cultural decoration and garden greening landscapes. These findings are consistent with the results of the SBE comprehensive evaluation, indicating that the combined SBE–SD method and eye movement analysis is a feasible approach for landscape experience evaluation, achieving the unity of subjective assessment and objective evaluation. The results contribute to the improvement of heritage landscape design and management.

Optimizing the design of fortress tour routes and landscape planning

Yi’an fortress possesses abundant, authentic historical information and is highly recognized for its landscape, but it lacks a comprehensive protection and development plan. The distinctive characteristics of different regions and types of landscapes have not been fully utilized. The research suggests landscape enhancement strategies tailored to various areas. These include enhancing the cultural and aesthetic appeal of natural ecological areas, enriching the diversity and liveliness of main building areas, and enhancing the visual and experiential quality of heritage entrances and Residential Living areas. The specific content is as follows:

-

1)

Enhancing the natural ecological area

The study found that the natural ecological area of the Yi’an Fortress was the least attractive to viewers. This is because historical heritage protection often overlooks the natural environment, and this area’s cultural and aesthetic qualities lag behind other areas, lacking distinctive features to capture the viewer’s attention and encourage them to linger.

To address this, landscape enhancement should avoid simply replicating urban greening methods. Instead, it can retain the soft revetments while enriching the vegetation and create a regional characteristic and recognizable rural cultural landscape by drawing on elements such as ancient trees, agriculture, and fisheries. Additionally, by taking advantage of the strong sense of spatial scale, coordinating near and distant landscapes can provide viewers with better comfort and aesthetics.

-

2)

Enhancing the core architectural area

The core building area is the most focused, where the architectural heritage such as the Dressingroom Tower, Small Ancestral Hall, and Grand Ancestral Hall have intact features and exquisite forms, forming an excellent visual scale that attracts viewers. This area also provides a solid historical experience for viewers.

However, the landscape aesthetics of this area are somewhat lacking, and the overall atmosphere is relatively solemn. Therefore, while maintaining the visual advantages of the architectural heritage landscape, it can be combined with cultural decorative landscapes and garden landscapes to enhance the area’s vitality. This can also increase the efficiency of space utilization as a venue for cultural display, education, and sightseeing.

-

3)

For the heritage entrance area and residential living areas

The overall visual perception of these areas is good but lower than that of the core building area. The landscape culture of the heritage entrance area is relatively poor. It is necessary to preserve and restore the historical architectural sites, integrate more historical elements, enrich the green plant landscapes, and pay attention to their scale, color, and form. The landscape aesthetics of the residential areas are also poor. Although the existing stone roads continue the original street and alley space system with a strong sense of order, the natural environment, cleanliness, and comfort are lacking. The vitality of the regional life is reduced. It is necessary to beautify the area, enrich the production and living scenes, increase intangible cultural activities, enhance the perception and experience of Subjects, and promote the sustainable protection of the heritage landscapes.

Limitation

-

(1)

Participant selection: this study evaluated the landscape experiences of different areas and types within the Yi’an Fortress, but did not analyze factors such as the gender and age of the participants. The selection of Subjects in this study aimed for a gender ratio closer to 1:1, with diverse professional backgrounds. However, previous research has shown that males tend to exhibit higher preferences for landscape diversity than females [62]. Additionally, the preferences of residents who have previously visited the Yi’an fortress or its different regions may vary, especially regarding architectural and cultural landscape appreciation. Subsequent research can provide more comprehensive experiential evaluations by including these different types of Subjects.

-

(2)

Landscape classification limitations: the classification of landscape types in this study was limited by the capabilities of the eye-tracking equipment to delineate regions of interest accurately. The classification was based solely on the area occupied by different landscape types within the image, which may not capture the nuances of the individual landscape elements. To obtain more precise evaluation results, future studies can consider combining the eye tracking data with other physiological response measurement instruments, such as brainwave and electroencephalography (EEG) data, to enable a more detailed and comprehensive analysis of the landscape elements and their impact on the viewers’ experiences.

These additional considerations regarding participant selection and landscape classification methods can help enhance the depth and accuracy of the experiential evaluation of the Yi’an Fortress heritage landscape in future research.

Conclusions

Heritage landscapes possess profound historical and cultural connotations, where the landscape content has visual influence and encompasses non-visual Spiritual experience. The outcomes of this research can directly inform the decision-making and strategies employed by the Yi’an fortress management authorities. By understanding the nuanced differences in visual experiences across the site’s various landscape elements, they can prioritize and tailor their conservation and development efforts to maximize public satisfaction and maintain the site’s distinctive cultural identity. Beyond the specific case of the Yi’an fortress, the integrated “subjective + objective” evaluation framework demonstrated in this study presents a robust and versatile methodology that can be adapted for assessing the visual experiences of heritage landscapes more broadly. Combining qualitative and quantitative assessments, this multi-dimensional approach provides a comprehensive, evidence-based foundation for heritage conservation planning and management. The successful application of this method in the Yi’an fortress context suggests its potential value and transferability to other cultural heritage sites facing similar challenges of landscape homogenization and disconnection from public needs. This study evaluated the visual experience of heritage landscapes in different regions and types of Yi’an fortress, a historical heritage site, using a combined “subjective + objective” cognitive evaluation and visual perception framework. This framework integrates the SBE–SD method and Eye-Tracking Analysis. The main findings of this study are as follows:

-

1.

There are significant differences in landscape experiences among different regions of heritage sites. The visual experience score of the core building area of Yi’an Fortress is (1.01) > the heritage entrance area (0.897) > the residential area (0.841) > the natural ecological area (0.784). This indicates that natural ecological areas should become a focus of future protection and development work, with a particular need to strengthen landscape aesthetics and culture.

-

2.

The landscape experience scores provide insight into the reasons for differences in participants’ landscape experiences. Compared to cultural decorations and garden greening landscapes, the architectural heritage landscape of Yi’an Fortress achieved the highest experiential evaluation score due to its superior ‘landscape form’ factors. Conversely, garden greening landscapes received the lowest scores due to their poor performance in ‘landscape form’ and ‘landscape aesthetics’ factors. Heritage planners and managers at Yi’an Fortress might consider increasing vegetation diversity and enriching landscape layers to create a high-quality heritage environment.

-

3.

This study found that eye movement results aligned with comprehensive evaluation outcomes. This consistency indicates that the combined “subjective + objective” cognitive evaluation and visual perception framework, utilizing the SBE–SD method and eye tracking analysis, is a scientific and effective approach for assessing the visual experience of heritage landscapes. This research method can assist researchers, planners, and government departments in clarifying the visual quality of heritage sites and developing scientifically grounded planning and management solutions. Consequently, it provides a robust basis for heritage landscape protection and design.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Yao YF. The value and planning of archaeological sites. J Beijing Forest Univ. 1991;1:77–81.

Sauer CO. The morphology of landscape. Univ Calif Publ Geogr. 1925;2(2):46.

Cultural Exchange Bureau, Ministry of Culture. Selected works of the UNESCO convention on the protection of the world cultural heritage. Beijing: Law Press. 2006. p. 53–62.

Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(6):1161–78.

Li XY, Chen JY. A study on the perceptual difference of rural cultural landscape elements from the perspective of host-guest sharing: a case study of Huanglongyan Tea Culture Village in Nanjing. Mod Urban Res. 2024;1:125–32.

Liu WD, Chen BC, Zhang H, Meng ZB. A study on the cultural design of cultural landscape driven by place: a case study of the Lingyan Temple West Road project in Yingkou. Chin Landsc Archit. 2022;38(S2):41–6. https://doi.org/10.19775/j.cla.2022.S2.0041.

Luo YS, Shen SY, Zhan W. Evaluation of cultural landscape experience in Zhangguyingcun based on SD and eye-tracking analysis. Chin Landsc Archit. 2022;38(05):98–103. https://doi.org/10.19775/j.cla.2022.05.0098.

Liu FF, Kang J, Wu Y, Yang D, Meng Q. What do we visually focus on in a world heritage site? A case study in the historic centre of Prague. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01411-1.

Steinhardt U. Applying the fuzzy set theory for medium and small l scale landscape assessment. Landsc Urban Plan. 1998;41:203–8.

Zhang YQ, Xu YY, Zhou WZ. A study on the evaluation of rural landscape based on Jiangnan culture. World Agric. 2021;6:92–9. https://doi.org/10.13856/j.cn11-1097/s.2021.06.010.

Daniel TC, Boster RS. Measuring landscape esthetics: the scenic beauty estimation method. New York: Plenum Press; 1976.

Buhyoff GJ, Leuschner WA, Arndt LK. Replication of a scenic preference function. Forest Sci. 1980;26(2):227–30.

Osgood CE. Semantic differential technique in the comparative study of cultures. Am Anthropol. 1964;66(3):171–200.

Yu KJ. Research on the evaluation of natural landscape quality—BIB-LCJ aesthetic judgment measurement method. J Beijing For Univ. 1988;2:1–11.

Cao J, Liang YR, Zhang JH. Preliminary investigation and evaluation of landscape in nature reserves in Beijing. Chin Landsc Archit. 2004;7:77–81.

Lu ZS, Zhao DH, Zhao RS, Ren BS. Practice and research on forest management in Zhongshan Scenic Area, Nanjing, East China. For Manag. 1991;1:1–619.

Hu JL, Chen HT, Li P, Qing G, Luo N. Evaluation and optimization of visual landscape in Guilin National Forest Park in winter based on GIS and SBE method. J Northwest For Univ. 2023;38(05):262–9.

Duchowski AT. A breadth-first survey of eye-tracking applications. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2002;34(4):455–70.

De-Lucio JV, Mohamadian M, Ruiz JP, Banayas J, Bernaldez FG. Visual landscape exploration as revealed by eye-movement tracking. Landsc Urban Plan. 1996;34(2):142.

Nassaueer JI. Cultural principle of the landscape. Landsc Ecol. 1995;10(4):229–37.

Arriaza M, Cañas-Ortega JF, Cañas-Madueño JA, Ruiz-Aviles P. Assessing the visual quality of rural landscapes. Landsc Urban Plan. 2004;69(1):115–25.

Wu Y, Li N, Xia L, Zhang S, Liu F, Wang M. Visual attention predictive model of built colonial heritage based on visual behaviour and subjective evaluation. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2023;10(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02399-y.

Cloquell-Ballester VA, del Carmen T-S, Cloquell-Ballester VA, Santamarina-Siurana MC. Human alteration of the rural landscape: variations in visual perception. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2012;32(1):50–60.

Sottini VA, Bernetti I, Pecchi M, Cipollaro M. Visual perception of the rural landscape: a study case in Val di Chiana aretina, Tuscany (Italy). Aestimum. 2018. https://doi.org/10.13128/Aestimum-23967.

Cosgrove D. Social formation and symbolic landscape. London: Groom Helm; 1984. p. 56–84.

Rambonilaza M, Dachary-Bernard J. Land-use planning and public preferences: what can we learn from choice experiment method? Landsc Urban Plan. 2007;83:318–26.

Zhou XQ. New progress in the study of rural landscape in Western countries. Areal Res Dev. 2007;3:85–90.

Ryan RL. Preserving rural character in New England: local residents’ perceptions of alternative residential development. Landsc Urban Plan. 2002;61(1):19–35.

Zhangpu County Chronicles Compilation Committee. Zhangpu County chronicles. Beijing: Fangzhi Press; 1998.

Li CC. Prediction of the optimal number of people required for video significant eye movement experiment. PhD dissertation. Hangzhou: Hangzhou University of Electronic Science and Technology; 2019.

Zhang JH. Investigative analysis method 16 in planning and design: SD method. Chin Landsc Archit. 2004;20(10):57–61.

Dupont L, Antrop M, Van Eetvelde V. Does landscape related expertise influence the visual perception of landscape photographs? Implications for participatory landscape planning and management. Landsc Urban Plan. 2015;141:68–77.

Zhang WD, Liang Q, Fang HL, Zhang QF. An eye-movement research on city greening landscape appreciation. Psychol Sci. 2009;4:801–3.

Habron D. Visual perception of wild land in Scand. Landsc Urban Plan. 1998;42(1):45–56.

Li ZP, Liu LM, Xie HL. Methodology of rural landscape classification: a case study in Baijiatuan Village, Haidian District, Beijing. Resour Sci. 2005;27(2):167–73.

Zube EH, Sell JL, Taylor JG. Landscape perception: research, application and theory. Landsc Plan. 1982;9(1):1–33.

Hu Z, Liu PL, Deng YY, Zheng WW. Research on the identification and extraction method of the genetic characteristics of traditional settlement landscape. Acta Geogr Sin. 2015;35(12):1518–24. https://doi.org/10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.2015.12.004.

Liu PL. Construction and application research of the gene map of traditional settlement landscape in China. PhD dissertation. Beijing: Peking University; 2011.

Liu PL. Gene expression and landscape recognition of the cultural landscape of ancient villages. J Hengyang Normal Univ. 2003;4:1–8.

Bulut Z, Yilmaz H. Determination of landscape beauties through visual quality assessment method: a case study for Kemaliye (Erzincan/Turkey). Environ Monit Assess. 2008;141(1):121–9.

Palmer JF, Hoffman RE. Rating reliability and representation validity in scenic landscape assessments. Landsc Urban Plan. 2001;54(1–4):149–61.

White MP, Cracknell D, Corcoran A, Jenkinson G, Depledge MH. Do preferences for waterscapes persist in inclement weather and extend to sub-aquatic scenes? Landsc Res. 2014;39(4):339–58.

Byrne MD, Byrne MD, Anderson JR, Douglass S, Matessa M. Eye tracking the visual search of click-down menus. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 1999. p. 402–9.

Gao Y, Zhang T, Zhang W, Meng H, Zhang Z. Research on visual behavior characteristics and cognitive evaluation of different types of forest landscape spaces. Urban For Urban Green. 2020;54: 126788.

Gobster PH, Nassauer JI, Daniel TC, Fry G. The shared landscape: what does aesthetics have to do with ecology? Landsc Ecol. 2007;22(7):959–72.

Yu KJ. The main schools and methods of landscape resource evaluation. In: Proceedings of young landscape architects (collection), urban design information materials. 1988. p. 31–41.

Zhu JF. Research on the quality of forest recreation space in Beijing based on SD method. PhD dissertation. Beijing: Beijing Forestry University; 2012.

Jiao MY, Gao F, Hao PY, Dong L. Evaluation of urban linear park vegetation landscape based on SD method. J Northwest For Univ. 2013;28(5):185–90.

Xu J, Jiang P. A survey of visual saliency and salient object detection methods. J Shandong Univ. 2018;54(3):28–37. https://doi.org/10.6040/j.issn.1671-9352.0.2018.601.

Jiang Y, Chen L, Grekousis G, Xiao Y, Ye Y, Lu Y. Spatial disparity of individual and collective walking behaviors: a new theoretical framework Transp. Res Part D Transp Environ. 2021;101:103096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2021.103096Get.

Avolio ML, Pataki DE, Pincetl S, Gillespie TW, Jenerette GD, McCarthy HR. Understanding preferences for tree attributes: the relative effects of socio-economic and local environmental factors. Urban Ecosyst. 2015;18(1):73–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-014-0388-6.

Bojko A. Informative or misleading? Heatmaps deconstructed. In: International conference on human–computer interaction. Berlin: Springer; 2009. p. 30–9.

Holmqvist K, Nyström M, Andersson R, Dewhurst R, Jarodzka H, Van de Weijer J. Eye tracking: a comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oup Oxford;2011.

Kiefer P, Giannopoulos I, Raubal M, Duchowski A. Eye tracking for spatial research: cognition, computation, challenges. Spat Cogn Comput. 2017;17(1–2):1–19.

Wen Y, Albert I, Von Haaren C. Landscape visual characteristics influence users’ aesthetic preferences: a review. Landsc Urban Plan. 2021;205: 103950.

Poole A, Ball LJ. Eye tracking in HCI and usability research. Encycl Hum Comput Interact. 2006;1:211–9.

Orquin JL, Holmqvist K. Threats to the validity of eye-movement research in psychology. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50(4):1645–56.

Guo SL, Zhao NX, Zhang JX, Xue T, Liu PX, Xu S, Xu DD. Landscape visual quality assessment based on eye movement: college student eye-tracking experiments on tourism landscape pictures. Resour Sci. 2017;39(6):1137–47. https://doi.org/10.18402/resci.2017.06.13.

Smith J, Brown K, White L. Visitor satisfaction in Yellowstone National Park. Tour Manag. 2019;70:1–12.

Jones M. The aesthetic and cultural value of the Great Wall of China. Cult Herit Stud. 2021;45:153–67.

Brown A, Johnson P. Emotional responses to natural landscapes: a study of the Grand Canyon. J Environ Psychol. 2020;68:101–12.

Jie B. Research on visual perception and evaluation of traditional village landscape in Huizhou. PhD dissertation. Hefei: Anhui Jianzhu University; 2023. https://doi.org/10.27784/d.cnki.gahjz.2023.000413.

Acknowledgements

Hereby thank the Fujian Provincial Office of ethnic and religious affairs for providing the list of ethnic minorities and relevant data free of charge.

Funding

This research is funded by Zhejiang University: 876-211 Class Project, funding project code: 113000*1942221R1/007, and Anhui Provincial Key Laboratory of Huizhou Architecture 2024 Open Project, funding project code: 2024HPJZ-KF01, Zhejiang Province Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project “A study on climate-resilient design decisions for low-rise residential buildings in northern Zhejiang cities from a multi-agent perspective”, grant number 23NDJC105YB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiang XU: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Rui DONG: data curation, formal analysis, validation, writing—review and editing. Zhixing LI: data curation, formal analysis, validation, Yuxiao JIANG: writing—review and editing, data curation. Paolo Vincenzo GENOVESE: writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin University, with the approval number No. TJUE-2024-366.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Dong, R., Li, Z. et al. Research on visual experience evaluation of fortress heritage landscape by integrating SBE–SD method and eye movement analysis. Herit Sci 12, 281 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01397-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01397-w