- Review

- Open access

- Published:

Research on global cultural heritage tourism based on bibliometric analysis

Heritage Science volume 11, Article number: 139 (2023)

Abstract

Cultural heritage is the sum of material wealth and spiritual wealth left by a nation in the past. Because of its precious and fragile characteristics, cultural heritage protection and tourism development have received extensive global academic attention. However, application visualization software is still underused, and studies are needed that provide a comprehensive overview of cultural heritage tourism and prospects for future research. Therefore, this research employs the bibliometric method with CiteSpace 5.8. R2 software to visualize and analyze 805 literature items retrieved from the SSCI database between 2002 and 2022. Results show, first, scholars from China, Spain, Italy have published the most articles, and Italian scholars have had the most influence. Second, Hong Kong Polytech University, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Jinan University have had significant influence on cultural heritage tourism research. Third, Annals of Tourism Research is the most cited journal in the field. Influenced by politics, culture, and technology, sustainable development and consumer behavior have become key topics in this field over the past 21 years. Fourth, tourist satisfaction, rural development, cultural heritage management are the key research frontiers. Fifth, in future, cultural heritage tourism should pay more attention to micro-level research, using quantitative methods to integrate museums, technology, and cultural heritage into consumer research. The results offer a deeper understanding of the development and evolution of the global cultural heritage tourism field from 2002 to 2022. At the same time, our findings have provided a new perspective and direction for future research on global cultural heritage tourism among scholars.

Introduction

Cultural heritage is shared wealth with outstanding universal value, the precious wealth left by human ancestors to future generations, and a non-renewable precious resource [1]. The year 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the implementation of the World Heritage Convention, which UNESCO adopted in 1972 to protect, utilize, and inherit cultural heritage under the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, and to make positive contributions to the protection and restoration of the common heritage of all mankind. Cultural heritage is of two types: tangible and intangible. As of February 2022, there are 897 cultural heritage sites in 167 countries on five continents. As countries around the world pay more and more attention to cultural heritage, cultural heritage protection in connection with tourism development has become a new area of concern for scholars all over the world. The year 2002 saw the publication of the first study in the field of cultural heritage tourism [2]. At this point, a review of the research on cultural heritage tourism published over the past 21 years will help us to understand and grasp the overall trends in global cultural heritage tourism development.

Cultural heritage embodies the wisdom and crystallization of human development, carrying the genes and bloodline of human civilization, which need to be protected, displayed, and disseminated for their cultural value. From a fundamental perspective, cultural heritage tourism is a form of tourism that transforms historic and cultural assets into commodities in order to attract tourists [3]. Since 1970, European and American countries have continuously innovated cultural heritage tourism activity models, promoting it as a popular mode of tourism, while also driving research into cultural heritage tourism [4, 5]. As one of the most vital topics in cultural heritage research, cultural heritage tourism has gradually diversified from the perspective of studying visitors and local residents of heritage sites [6, 7]. Moreover, from a research methods standpoint, qualitative and quantitative methodologies coexist [8, 9] and have progressed towards incorporating mixed research methods as a new trend [10]. In addition, cultural heritage tourism practice mainly includes two aspects: dynamic protection of cultural heritage [11] and tourism development [12]. Although current research provides useful guidance for informing cultural heritage tourism development and preservation, there is still a lack of an overall review of current cultural heritage tourism related research. Nevertheless, scholars have suggested that analyzing and reviewing existing literature can provide insights into the hotspots and trends within a research field. This not only serves as a reference for related studies [13], but also provides guidance for practical applications [14]. It can be seen that conducting a comprehensive review of cultural heritage tourism is of great importance.

With the growing number of studies and expanding research areas in cultural heritage tourism, existing literature reviews on this topic face difficulties in objectively and comprehensively reflecting the trends and shifts in research focus. Therefore, this study used the CiteSpace 5.8.R2 visual analysis software. It can be used to visualize knowledge structure, research hotspots, and the evolution of research topics, thereby helping researchers to obtain an overview of a field, find its classic literature, explore its research frontiers, and explain the evolution of its trends [15]. Through comparing with similar studies by other scholars, we found that most of the research on this topic focuses on the following questions [13, 16, 17].: (1) which literature has been groundbreaking and landmark, (2) which literature has played a key role in the advancement of the field, (3) which themes are dominant in the entire research area, and (4) what is the knowledge base of the field and how has the forefront of research evolved. Therefore, to better address these four key areas of literature review, this study obtained data on the literature related to cultural heritage tourism from 2002 to 2022 from the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) database. The data was then subjected to visual analysis using CiteSpace 5.8.R2 software, which enabled the objective review of a field's knowledge structure, research status, and trends by drawing knowledge maps. This study is committed to achieving the following four research objectives in order to address the aforementioned issues: (1) to establish the number of representative publications on cultural heritage tourism; (2) to explain the distribution and co-citation of authors and research institutions; (3) to identify current research hotspots in the field of cultural heritage tourism and trace their evolution from 2002 to 2022; and (4) to determine the frontiers and trends of cultural heritage tourism research. The results reveal future research prospects for cultural heritage tourism and will provide a reference for the construction of a theoretical system in the field of cultural heritage tourism [18].

Current state of research

Cultural heritage tourism relies on the unique historical architecture, religious beliefs, traditional cuisine and other cultural characteristics of the destination to attract tourists for sightseeing and experience. It has become one of the fastest-growing and most ideal forms of modern tourism. Meanwhile, cultural heritage tourism has gradually become an interdisciplinary field of psychology, economics, management, etc. [19,20,21], demonstrating a good academic ecology of mutual integration and development. Current research in cultural heritage tourism mainly revolves around research perspectives, methods, and cultural heritage preservation and tourism development.

Cultural heritage tourism research perspectives

From the perspective of researching cultural heritage tourism, it can generally be divided into two views: that of tourists and that of residents of the heritage sites. On one hand, tourists are the participants of tourism activities and have always been a focus of research in academia. As DallenJ explained the four forms of heritage experience and proposed personalized heritage tourism for tourists with great potential in future [22]. Meanwhile, Yaniv et al. challenged the notion that heritage tourism is only represented by visitors to heritage sites, pointing out the necessity to pay attention to the perception of tourists and conduct studies on their behavior [6]. On the other hand, the positive actions of residents living in heritage areas contribute to the sustainable development of cultural heritage tourism [7]. The perception of tourists impact on residents plays an important mediating role in shaping community attachment, environmental attitudes, and supporting economic benefits from tourism development [23].

Research methods of cultural heritage tourism

From the perspective of research methods in cultural heritage tourism, the measurement methods and models used vary depending on the researcher's perspective. Existing literature on cultural heritage tourism-related research methods can generally be divided into quantitative research methods, qualitative research methods, and mixed research methods. Firstly, quantitative research methods play an important role in current cultural heritage tourism-related research. Existing studies have used research methods such as SEM [24, 25], cluster analysis [26], experimental method [27], meta-analysis, etc. to conduct a large amount of research on cultural heritage tourism. Secondly, with the interdisciplinary integration, qualitative research methods have also been introduced into the field of cultural heritage tourism research. Qualitative research methods such as textual analysis [9], case study [28, 29], grounded theory analysis [8], QCA research method [30], etc. have conducted in-depth analysis of the field of cultural heritage tourism. In addition, to promote further in-depth research on cultural heritage tourism, mixed research methods have gradually become a hot topic of concern for scholars. For example, Rasoolimanesh et al. adopted a mixed research method combining PLS-SEM and fsQCA to conduct in-depth analysis of cultural heritage tourism driving behavior intention [10].

Research on cultural heritage protection and tourism development

With the attention paid to cultural heritage, its economic value, cultural value and social value have been widely paid attention to, which also makes cultural heritage protection and tourism development research become the current research focus. On the one hand, live protection of cultural heritage. Antonio et al. took Venice, a water city in Italy, as the research object and, relying on the vicious cycle model of tourism development, pointed out that with the development of tourist destinations, emerging groups keen on hiking have a great impact on the weakening of the city's attraction [31]. However, van et al. took World heritage cities as research objects and pointed out that when costs exceed benefits, tourism development is no longer sustainable, so it is necessary to intervene [32]. In addition, Christina et al. proposed five levels of heritage protection and development through the analysis of stakeholders [11]. On the other hand, cultural heritage tourism development. By studying tourism development cases of cultural heritage, Esteban et al. pointed out the influence of community role on tourism development and concluded the mutual influence between community identity and tourism [12]. At the same time, Arwel and Joan et al. discussed the tourism potential of the mining area, proposed that it should be included in the category of heritage tourism, and actively participated in the development of industrial heritage tourism sites [33]. Antonio et al. pointed out through empirical analysis that the basis for effective development of tourist destinations is whether tourism products can hit the softest places in tourists' hearts and whether they have internal accessibility [34].

Materials and methods

This section explains the selection of the research tools, analysis of the data sources, and main research methods used in this study.

Selection of research tools

This study used the CiteSpace 5.8.R2 visual analysis software developed by the team of Professor Chen Chaomei of Drexel University. The software, which was developed by drawing on scientometrics and knowledge visualization, is capable of processing large amounts of scientific literature data objectively [35,36,37]. To date, CiteSpace has been used by users in more than 100 countries and regions around the world, and has published more than 28,000 related academic papers. Researchers can use the CiteSpace software to perform co-citation analysis, co-occurrence analysis, cluster analysis, and keywords burst analysis for scientific research purposes [37]. In addition, it can be used to visualize knowledge structure, research hotspots, and the evolution of research topics, thereby helping researchers to obtain an overview of a field, find its classic literature, explore its research frontiers, and explain the evolution of its trends [37].

Analysis of data sources

Table 1 summarizes the data collection procedure for this study. The data were retrieved from the Web of Science SSCI on January 26, 2022. They cover all the relevant literature on cultural heritage tourism from January 1, 2002, to January 26, 2022. There were two main reasons for selecting the literature in SSCI as the data source: (1) SSCI’s authority as the most authoritative database in the field of global social sciences, and (2) SSCI’s extensiveness, with more than 3,200 papers from authoritative academic journals of in 56 disciplines in the field of social sciences. The year 2002 was chosen as the starting point for this study because the first academic paper in the field of global cultural heritage tourism was published in SSCI in that year.

The retrieval criteria for this study were based on subject-word retrieval, with topic = “Cultural Heritage” + “Tourism”, and a total of 825 related items of literature were obtained. A total of 20 book reviews, conference proceedings, and editorial materials were excluded from the data, yielding a set of 805 papers as the research object (Additional file 1 and 2). To ensure the accuracy of the data, the titles and abstracts of all the articles were reviewed individually to confirm that the data met the requirements of the study. The article data were stored in plain text format (full records and cited references) for subsequent data analysis.

Main research methods

The bibliometric method was used to conduct scientific research cooperation analysis on the literature. This took the form of analysis of cooperation between publishing authors, publishing institutions, and countries (regions); co-citation analysis, including citation analysis of documents, authors, and journals; and cluster analysis of the literature and keywords.

Collaborative analysis focuses on how researchers work together to produce new scientific knowledge [38]. A bibliometric approach analyzes joint research in a research field in terms of collaborative networks among authors, institutions, and countries.

Co-citation analysis [39] involves comparing lists of citations in the SSCI and counting the entries to determine the co-citation frequency of two scientific papers. This generates a network of co-cited papers for specific scientific disciplines. Clusters of co-cited papers provide new ideas for the professional structure of research science and new methods for index and SDI configuration file creation.

Co-occurrence analysis quantifies information in various information carriers, and is generally used to reveal the hidden meaning of the co-occurrence of keywords and topics. Keyword co-occurrence analysis can clarify the structure of scientific knowledge and is an effective way to identify research hotspots and discover researchtrends [17].

Cluster analysis depends on clustering, the process of dividing a set of objects into groups. Each element in a cluster has a high degree of similarity, whereas the degree of difference between different clusters is high [35]. Professor Chen has pointed out that in CiteSpace, the cluster labels are all from the document where the citation is located, and the extraction is performed by extracting the title or abstract or keyword in the cited document [40].

Results

This section considers three topics: (1) publishing volume analysis, to better understand the number of published articles; (2) collaboration analysis, to identify relationships among authors, academic institutions, and countries; and (3) co-citation analysis, to determine which scholars and academic journals are most influential.

Publishing volume analysis

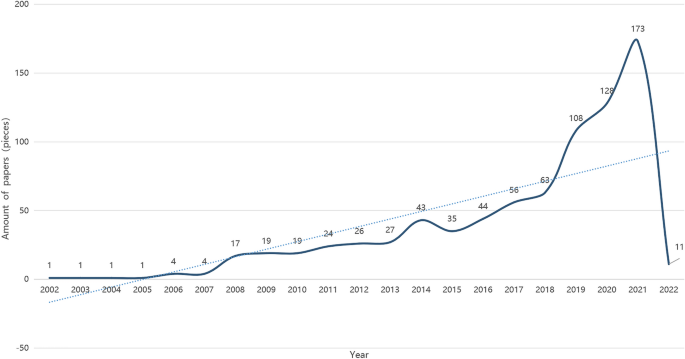

To gain a preliminary understanding of the overall development trend in cultural heritage tourism from 2002 to 2022, we searched SSCI for cultural heritage tourism publications in the past 21 years. The search results are shown in Fig. 1. The literature on global cultural heritage tourism shows that over the period the number of publications followed an upward trend with slight fluctuations. In 2002, only one article on cultural heritage tourism was published; it took the form of an empirical study of the willingness to protect and develop cultural heritage sites in western Kenya, with an exploration of how to develop and plan cultural heritage tourism [41]. Subsequent international cultural heritage tourism research can be divided into three phases. The first phase, from 2002 to 2007, is one of slow growth. Although the number of published papers was relatively low, with four papers or fewer each year, the overall trend was on the rise. Reflecting the fact that global cultural heritage tourism research was still in its infancy at this stage, only scholars in a small number of countries with substantial cultural heritage carried out research. The second stage, from 2008 to 2016, was one of stable growth. The number of articles published continued to increase, indicating that researchers around the world were beginning to realize the importance of developing cultural heritage tourism for economic growth and cultural protection, and beginning to get involved in cultural heritage tourism research. The third stage, from 2014 to 2022, was one of rapid growth, with 173 research papers published in 2021 alone. This indicates that cultural heritage tourism is receiving the attention of global researchers from different disciplinary backgrounds and different perspectives.

Cooperation analysis

Authors and author collaboration

The number of papers published by an author in a research field reflects that author’s core position in the field. The co-occurrence of the co-authors of a paper reflects the strength of their cooperation in the research field. By selecting the node type column of the CiteSpace 5.8.R2 software, the time period 2002–2022, and the “go” cluster, we obtained a map of collaborations between authors. Taking into account the overall publication volume of cultural heritage tourism, according to Price’s law, the core authors in the field of cultural heritage tourism should have at least the number of publications. The calculation formula is as follows:

where N1 is the minimum number of papers that the core author should publish, and Nmax is the number of papers published by the author with the most papers in this research field [42]. According to the search, the author with the largest number of papers in the field of cultural heritage tourism is Zhang Mu, with a total of seven papers (N1 = 0.749*(7)1/2 = 1.982), and the number of publications by the core authors in cultural heritage tourism is two or more. A total of 51 authors published two or more papers, yielding 122 papers and accounting for 16.05% of the papers published in the field of cultural heritage tourism. Comparison with the core author group, which should account for 50% of the total published papers in the research field, indicates that there is still a big gap. Thus, the results show that global cultural heritage tourism research has begun to take shape but that a stable core author group has not yet formed.

The most authors have conducted academic research independently and have weak cooperative relationships. Nevertheless, small cooperative groups can be identified. For example, Zhang Mu has cooperated with Rob Law on a number of articles (including “Using Content Analysis to Probe the Cognitive Image of Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism: An Exploration of Chinese Social Media”; “From Religious Belief to Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism: A Case Study of Mazu Belief”; “Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity”; and “Sustainability of Heritage Tourism: A Structural Perspective from Cultural Identity and Consumption Intention”), which indicates a relatively close partnership [42,44,45,46]. The relationship between authors in such cases is usually a teacher–student relationship, but may also be a relationship of belonging to the same institution.

The greater the betweenness centrality of a node in the network, the greater the role it plays in communication among other nodes [47]. In Table 2, the centrality of each author in the field of cultural heritage tourism is 0. This confirms that the cooperation between authors in the field of cultural heritage tourism is low and needs to be strengthened [48].

Issuing organizations

A comprehensive grasp of which institutions are involved in cultural heritage tourism research helps to clarify the general situation of cultural heritage tourism research and international cooperation between institutions. Therefore, this study carried out an institution-based search in CiteSpace 5.8.R2. Taking the institution as the network node, 369 nodes were generated, representing 369 core research institutions in the field of cultural heritage tourism research. These core research institutions feature in many core collaborative networks (Table 3).

From 2002 to 2022, the research field of cultural heritage tourism involved 369 major researchinstitutions. Of these institutions, 11 published five or more papers, accounting for 10.68%of the total number of papers published. Hong Kong Polytech University published the largestnumber of papers (1.86% of the total), followed by University of Cordoba, the Chinese Acadmy of Sciences, Kyung Hee University, and University of Extremadura. Three institutions, Hon Kong Polytech University, Jinan University, and Australian National University, had the strongest centrality (0.01), indicating that they have a strong influence in the field of cultural heritage tourism research. Sun Yat Sen University and Griffith University have also published many papers.

Countries and regions

To understand the cooperation between countries and the influence of countries in the field of cultural heritage tourism, this study used the country option through the node type of CiteSpace 5.8.R2 software to obtain the national cooperation map from 2002 to 2022. Using the social network analysis function of CiteSpace software, we explored the social network relationships of different countries and regions, which directly reflects the cooperation between them, and on that basis we identified differences in their degree of influence [49].

The cluster map reflects structural features, highlighting key nodes and important connections. Each node in the network diagram represents a country (or region), and the connecting line represents the cooperation between two countries; the thicker the line, the closer the cooperation. The size of the annual ring indicates the number of publications; the larger the annual ring, the more publications. The graph generated 84 nodes and 264 connecting lines, indicating that from 2002 to 2022 the authors who published literature related to cultural heritage tourism came from 84 countries. The network density cooperation of different countries on cultural heritage tourism is 0.0757. China is the country that has published the most research papers in the field of cultural heritage (125), accounting for 16.45% of the total number of documents, more than any other country. Spain, Italy, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia follow, accounting for 12.50%, 11.84%, 10.00%, 8.68%, and 7.11%, respectively. Centrality refers to the importance of a node in a network (Table 4); the higher the correlation between each node, the higher its centrality and the more important the node is in the field. The centrality values for Italy and the United States are 0.34 and 0.26, respectively, indicating that Italy and the United States have had more cooperation with other countries in the field of cultural heritage tourism. Although China had a higher number of papers, its centrality was lower (0.07), which suggests that its cooperation with other countries in cultural heritage tourism research has been relatively weak.

Co-citation analysis

To understand author and journal status systematically, we selected the “cited author” and “cited journal” options in the node type column of CiteSpace 5.8.R2 software and set the time to 2002–2022. We thus obtained the network graphs of cited authors and academic journals summarized in Tables 5 and 6. Through analysis of journal co-citations, a knowledge base of a research field can be obtained.

The three most cited authors are UNESCO (cited 129 times), E. Cohen (cited 90 times),andRICHARDS G(cited 87 times). The most cited journal is Annals of Tourism Research, with 441 citations and impact factors for 2018, 2019, and 2020 of 5.493, 5.908, and 9.011, respectively. Tourism Management, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Sustainability, and Journal of Travel Research follow, with 433, 202, 191, and 169 citations, respectively. The specific rankings of different influential authors and journals are given in Tables 5 and 6.

Keyword co-occurrence analysis

As Professor Chen has pointed out, analyzing keywords is the most suitable means to identify the evolution of this research field and related research hotspots and fronts [35]. In the following analysis, keywords are analyzed using CiteSpace 5.8.R2 to generate keyword co-occurrence maps, time zone maps, and cluster maps.

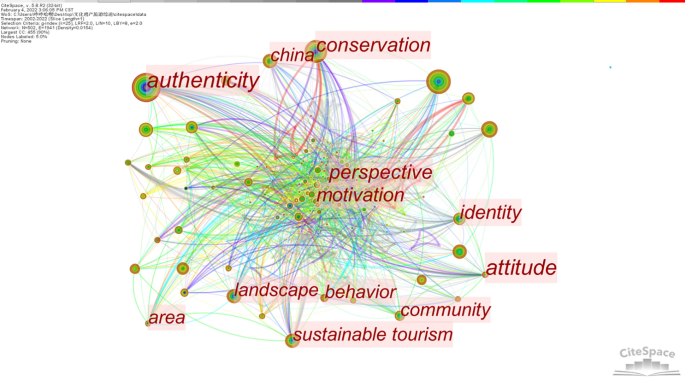

Co-occurrence analysis of high-frequency keywords can reveal research hotspots in the field of cultural heritage tourism [50]. Figure 2 gives the keyword co-occurrence map of cultural heritage tourism research keywords from 2002 to 2022, obtained by merging overlapping keywords while removing search terms. The five most frequent keywords with high centrality are authenticity (frequency = 90, centrality = 0.15), attitude (frequency = 28, centrality = 0.13), conservation (frequency = 57, centrality = 0.08), identity (frequency = 36, centrality = 0.08), and China (frequency = 46, centrality = 0.05). By applying criteria based on frequency and betweenness centrality [51], five research hotspots were extracted: authenticity, attitude, identity, conservation, and China. The following subsections consider these five hotspots in relation to articles by key scholars around the world.

Authenticity

Authenticity is recognized by a wide range of research scholars as a universal value that drives people to leave familiar regions and travel to far-flung places [52]. Authenticity research is essential for tourism in general and for heritage tourism in particular [53, 54]. The premise of protection is the maintenance of the authenticity of cultural heritage, which means avoiding overemphasis on economic value [55]. At present, the research hotspots of authenticity in the field of cultural heritage tourism focus on the following two aspects: what authenticity is [56,57,58], that is, the basic concept of authenticity, and what effect the authenticity of cultural heritage has on cultural heritage tourism [59,60,61,62] that is, whether authenticity can promote cultural heritage tourism. Authenticity is a concept that does not appear in UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage (ICH) discourse, but is emphasized in the official Chinese ICH discourse [63]. Since authenticity is a complex concept, it has different manifestations [64], and the inability of heritage managers to adopt a holistic approach to shaping the meaning of authenticity has resulted in inadequate definitions of the concept [56]. In recent years, some scholars have tried to establish an inclusive and comprehensive concept of authenticity, focusing on the perspective of tourists and on the materiality and immateriality of cultural heritage [65, 66]. Other scholars have considered authenticity in terms of subjectivity and objectivity. For example, Junjie Su proposed through empirical research that heritage practitioners describe the ability to create substantial object-related value through subjective authenticity. This approach illustrates how subjective authenticity can overcome the inappropriateness of materialism or objective authenticity [57]. In terms of the impact of authenticity on heritage tourism, most scholars focus on the psychological perception or behavior of consumers, such as satisfaction, engagement [59], and perceived value [62]. In exploring the relationship between authenticity and consumer psychology or behavioral intention, the empirical results show that authenticity has a significant impact on consumers’ psychological perceptions.

Attitude

Attitude is the psychological perceptions of consumers under the combined action of various internal and external factors such as tourism product quality or the tourism environment, and is an important predictor of behavior. In the field of cultural heritage attitude, the focus of research has been on the effect of individual characteristics on cultural heritage tourism and how to enhance consumer tourism attitudes. Kastenholz et al. identified three categories of outcomes with multiple behavioral attitudes that affect sustainability: in their study, one group showed a greater focus on the environment and cultural heritage, a second group showed the most sustainable behaviors overall, while a third group reported less sustainable behaviors globally [67]. Some scholars have carried out research from the perspective of residents of cultural heritage tourism destinations, for example by adopting a normative framework of values and beliefs to measure the intentions of Carthaginians to support sustainable cultural heritage tourism [68, 69]. In addition, scholars conducting empirical research on the internal and external factors that affect consumers’ tourism attitudes have concluded that perception control, tourism experience, and cultural tourism participation can strengthen tourists’ attitudes to cultural heritage tourism [25]. Attitude is an important issue for both tourists and residents of heritage sites. The question of how to enhance the attitude of tourists in cultural heritage sites while also strengthening the attachment of the residents to the cultural heritage of their hometown is fundamental to the ongoing protection of cultural heritage [70].

Conservation

Since the formulation and adoption of the World Heritage Convention in 1972, the protection of cultural heritage has attracted worldwide attention. Cultural heritage conservation can determine the cultural connotation of tourism to a certain extent, and it constitutes the internal demand for the development of in-depth tourism. Given the special role of fragile and non-renewable cultural heritage in modern tourism, there are particular issues facing the protection of cultural heritage [71]. Since cultural heritage is the vehicle for a deep integration of culture and tourism [70], it should be afforded special protection.

Current research hotspots can be divided into two categories, the first of which focuses on macro-level cultural heritage protection planning and measures. Snowball and Courtney have argued that protecting cultural heritage is a challenge for developing countries, more and more of which are linking small sites of mainly local significance into a heritage route and selling them as a package. However, this may actually have non-market value in protecting cultural capital, which will not only fail to generate economic value in the short term but may also endanger the sustainability of cultural heritage protection [72]. In this connection, scholars have taken the Saida Cultural Heritage and Urban Development (CHUD) project in Lebanon as a case study for analyzing the role of the tourism pathway approach in achieving sustainable urban development in historic areas [73]. The focus of the second category is the construction of cultural heritage evaluation indicators. Against the background of sustainable development, some scholars have drawn on culture-led regeneration projects to propose an evaluation index system capable of assessing the multidimensional benefits of cultural landscape conservation or appreciation, with a focus on the relationship between the tourism sector and climate change [74]. Other scholars have assessed cultural heritage risks. For example, in view of the risks to cultural and natural heritage, a landscape risk assessment (LRA) model and landscape decision support system (LDSS) have been developed through the MedScapes-ENPI project [75].

Identity

Identity is a research hotspot in the field of cultural heritage because identity can enhance the cultural confidence of heritage residents in cultural heritage, maintain cultural heritage, and promote local social and economic development while enhancing people’s national pride [51]. This hotspot emphasizes that in the development of cultural heritage tourism, tourists and local residents reach a common cognitive basis for cultural heritage through cultural identity, which guides tourists to consume and promotes national brand building [76]. For example, to encourage the continuous development of cultural heritage tourism [46] and to facilitate the formation of identity, Carnegie suggests reenacting cultural historical events [77]. In recounting the past and present of cultural heritage, it is helpful for the cultural heritage industry and tourists to understand the issues of authenticity and identity in the production and consumption of postmodern cultural heritage attractions [77]. In addition, Tian found that shaping the identity of tourists to Celadon Town, a classic scenic spot of ICH in Zhejiang Province, China, improved tourist satisfaction and loyalty to the destination [78].

China

Since China signed the World Heritage Convention in 1985, its contribution to world heritage has developed rapidly. As of July 25, 2021, the total number of world heritage sites in China had increased to 56, and the number of natural heritage sites had increased to 14. In terms of natural heritage sites, China ranks first in the world, making it a veritable center of heritage. As a result, the types of cultural heritage tourism found in China are diverse [79], providing research objects for cultural heritage research in different fields. The focus of studies on China has been to seek innovative means of developing high-quality cultural heritage tourism and of leading the development of global cultural heritage tourism [80]. Wang noted that tourism heritage has been destroyed during urban reconstruction in China [81], creating an urgent need to identify key stakeholders capable of meeting the responsibility to protect [81]. However, Yan and Bramwell argued that each country is in a unique position to determine how its cultural heritage should be used for tourism. It follows that, in response to the increasingly tense and unstable relationship between the traditional cultural activities of tourist sites and Chinese society, the Chinese government should streamline administration and delegate power in order to protect the cultural heritage [82].

Keyword time zone analysis

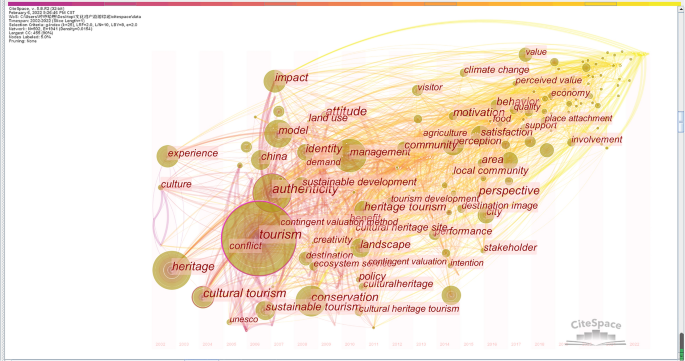

The time zone map generated by CiteSpace 5.8.R2 software shows the evolution of research hotspots over time. As shown in Fig. 3, this study divides the evolutionary process of cultural heritage tourism research into three stages, each of which is discussed in conjunction with representative articles and key events of the time.

First stage (2002–2007)

Cultural Heritage Protection. As Fig. 3 shows, the high-frequency keywords related to the first stage include cultural heritage tourism, sustainable, conflict, authenticity, and China. This indicates that the most obvious features of cultural heritage tourism in this period are cultural heritage protection and sustainable development, an outcome that is jointly determined by a number of factors. First, in 1992, the World Heritage Headquarters was established in Paris to be responsible for the coordination of world heritage-related activities, ensuring the implementation of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage and taking urgent action on threatened heritage. Then, on October 17, 2003, the 32nd General Conference of UNESCO adopted the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. In the wake of these developments, more and more researchers began to pay attention to the field of cultural heritage [51], and this marked a new stage in the protection of human cultural heritage. In 2002, the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (16th NCCPC), adopted continuous enhancement of the capacity for sustainable development as part of the overall goal of building a moderately prosperous society in China. Since 2006, the Chinese government has designated the second Saturday of every June as Cultural Heritage Day. In this context, Chinese academia has finally reached a consensus on cultural heritage and sustainable development. Cultural heritage and the natural environment on which it depends are the concentrated carriers of the cultural essence of all ethnic groups in the world, the precious wealth left to people by human ancestors, and a non-renewable precious resource. The development and utilization of cultural heritage by human beings should proceed under the premise of maintaining the authenticity and integrity of that heritage. In order not to damage the ecological balance and sustainable development capacity of the natural system, we must adhere to the path of sustainable development of cultural heritage [83].

Second stage (2008–2013)

Comprehensive Development of Cultural Heritage. As Fig. 3 shows, the related high-frequency keywords in the second stage include management, ecosystem, policy, landscape, community archaeology, agriculture, climate change, and tourism development. This indicates that the comprehensive development of cultural heritage and tourism industry emerged during the second stage. The present study offers two possible explanations for this emergence. On the one hand, with the development of social economy, environmental problems are becoming more serious, the tide of global warming is surging, and environmental problems are prominent on a global scale. In order to address environmental problems and promote the harmonious coexistence of man and nature, researchers began to explore green development models and paid more and more attention to cultural heritage, especially the economic, social, and ecological value and unity of cultural heritage in agriculture [84]. At the same time, there were attempts to link ecological structure and function with cultural values and interests through cultural ecosystem services, thereby facilitating communication between scientists and stakeholders [85]. On the other hand, steps were being taken to use archaeological knowledge to improve people’s attitudes to cultural heritage, to mobilize relevant individuals and groups to protect and preserve the cultural heritage of all mankind, and to understand the value of the past in order to avoid the tragic loss caused by the destruction of cultural heritage resources. As a result, more and more researchers became involved in community archaeology research [85, 86] As a new practice of archaeology and a new way of managing cultural heritage, the concept remained original, unbalanced, and pluralistic [87].

Third stage (2014–Present)

Consumer Behavior in Cultural Heritage Tourism. Figure 3 shows that the high-frequency keywords related to the third stage include behavior, perception value, customer satisfaction, motivation, consumption, place attachment, involvement, and consumer-based model. This reflects the fact that consumer behavior has become the most popular research in the field of cultural heritage tourism, followed by customer satisfaction [88], perception value [89, 90], place attachment [91], consumer perceived trust [92], and other psychological perspectives. It is precisely because of the interdisciplinary integration of psychology and management that widespread use has been made of consumer behavior as a perspective on business and tourism research, and that it has also become an important factor in the field of cultural heritage tourism research.

Keyword cluster analysis

Using CiteSpace 5.8.R2 software, the keywords were clustered and divided into topics. Through the CiteSpace clustering function, using keywords to extract information and using the logarithm likelihood ratio statistic (LLR) as the calculation method, 13 valid clustering labels were obtained (Silhouette > 0.5). After removing clusters with the same words as subject headings and a small number of articles, the first five clusters were selected for analysis. The results, which are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 7, include #0 Tourist satisfaction, #2 Rural development, #3 Cultural heritage management, #5 Stakeholders, and #8 China. The size of each cluster is determined by the number of articles it contains. To better interpret the clustering results, data have been selected at random as examples for each cluster.

#0 Tourist satisfaction. As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 7, tourism satisfaction has attracted the attention of scholars since 2016. Research on tourism satisfaction has focused on the application of empirical analysis methods. For example, in order to explore whether tourism commercialization can have a positive impact on tourists’ perceptions of authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural heritage tourism, Zhang et al. used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to conduct empirical analysis on 618 valid questionnaires collected to explore the relationship between variables [93]. To clarify the links between local community participation (LCP), authenticity, access to local products, destination image, tourist satisfaction and tourist loyalty, Jebbouri et al. conducted a survey of 406 respondents who visited Kaiping City, Guangdong Province, China, and tested their hypotheses empirically tested using moment structural analysis [94].

#2 Rural development. Research on rural development has focused on protection practices in relation to agricultural cultural heritage [95]. Some scholars have conducted case studies on the impact of cultural heritage on rural development. For example, Egusquiza et al. summarized the results of an analysis of data collected in 20 case studies to develop a multilevel database of best practices for extension in rural areas with common characteristics [96]. Meanwhile, Sardaro et al. conducted a case study on a collaborative approach to conservation of the most representative historic rural building types in Apulia, southern Italy, to identify successful conservation and management strategies [97]. Rautio investigated ethnic minority villages in Southwest China that have recently experienced a dramatic increase in cultural heritage. He argued that with the development of China’s new rural development policy and tourism, villages are being transformed into heritage sites that can protect the beauty of the countryside and the nation [98].

#3 Cultural heritage management. As Fig. 4 and Table 7 show, the theme of cultural heritage management has attracted the attention of scholars since 2016, and has become an important focus of academic research. Some scholars have concluded that a hybrid approach that unifies the fields of heritage management and sustainable tourism can realize the social value of heritage and sustainable tourism [99]. However, issues of low quality and vaguely defined management of cultural heritage sites persist. In this connection, Carbone et al. explored cultural heritage managers’ perceptions of quality and used a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods to identify four types of cultural heritage managers: reactive, silent, pragmatic, and enthusiastic [100].

#5 Stakeholders. As Fig. 4 and Table 7 show, the topic of stakeholders has attracted the attention of scholars since 2015. Research on stakeholders has focused on the relationship between people and cultural heritage. For example,Manyane drew on stakeholder theory and sustainability thinking to argue that rethinking the increasingly complex nature of borders and cultural heritage can enrich the supply of eco-culture based on a better understanding of cross-border rural tourism opportunities [101]. Ji et al. focused on the Grand Canal, which was designated as a World Heritage Site in 2014, applying stakeholder theory to explore how residents and non-residents may have different perceptions of the value and meaning of cultural heritage [102].

#8 China. As Fig. 4 and Table 7 show, China has become an important research object of cultural heritage tourism research. This is in line with the results of the keyword co-occurrence analysis, and reflects China’s vast and rich historical and cultural heritage [103]. In recent years, with the improvement of China’s comprehensive strength, the Chinese government has paid more attention to the ongoing protection, development, and utilization of cultural heritage. Cultural heritage protection sites have been established, providing a wide range of research objects for researchers in the field. At the same time, with the rapid development of China’s economy, now the second-largest in the world, the per capita income of Chinese residents has increased significantly, providing more potential customer groups for cultural heritage tourism [104]. With this rapid development of tourism resources and the tourism economy, the contradiction between economic growth and cultural heritage has become increasingly prominent [81]. Accordingly, exploring how to maintain China’s economic growth while protecting its cultural heritage is the mainstream of current research.

Trends in cultural heritage tourism research

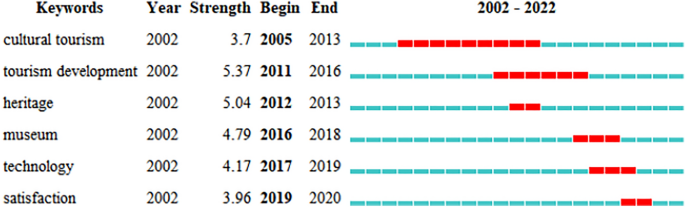

In CiteSpace, emerging words are keywords that increase rapidly in a given period of time. Research fronts are concepts and research directions that are constantly emerging and that represent frontier issues in the research field. Therefore, in the present study, mutation analysis of cultural heritage tourism keywords is an important indicator of the research frontier of a topic. In general, emerging keywords represent dynamic new directions in cultural heritage tourism research. In order to capture objectively the latest research frontier characteristics of cultural heritage tourism, we used the CiteSpace 5.8.R2 software settings for “keyword” to “node types”. The resulting knowledge map of keyword mutation rates identifies mutated words that began to appear from 2002 to 2022, generating a total of six knowledge maps of cultural heritage tourism keyword sequences. As Fig. 5 shows, these are cultural tourism, tourism development, heritage, museum, technology, and satisfaction.

In the field of cultural heritage tourism research, cultural tourism, heritage tourism, and tourism development have long been a focus. Understanding how to promote the experience of local culture in cultural heritage tourism is an important prerequisite for ensuring the long-term healthy development of cultural heritage tourism. In this connection, Chang et al. considered the natural tourist attractions, unique cultural performances, and diverse heritage goods that diverse indigenous communities offer. They applied a model of creative destruction to explore the impact of these developments on the Ainu community in Hokkaido, Japan [105].

The keywords of cultural heritage tourism changed abruptly in 2016. Museum, technology, and satisfaction became the latest keywords in cultural heritage tourism research. These keywords characterize the cutting-edge research of cultural heritage tourism, which indicates that scholars have been focusing on the impact of museum tourism, technology tourism, and consumer satisfaction on cultural heritage tourism. It also shows that with advances in science and technology, virtual reality technology has received more attention in the field of cultural heritage tourism [106,107,108]. Meanwhile, Dominguez-Quintero confirmed the direct and indirect effects of variable authenticity on satisfaction in its dual perspectives (objective and existential authenticity) in the context of cultural heritage tourism [61]. The present findings also shed light on the mediating role of quality of experience on authenticity and satisfaction.

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

In this study, the visual analysis software CiteSpace 5.8.R2 was used to carry out bibliometric analysis. Analysis of 805 papers on cultural heritage tourism research in the Web of Science SSCI from 2002 to 2022 yielded a visual network analysis graph that includes the distribution of published articles, the co-analysis of published authors, publishing institutions and countries, the co-citation analysis of published authors and published journals, keyword co-occurrence analysis, keyword time zone map analysis, keyword clustering graph analysis, and keyword emergence analysis. The conclusions can be grouped into four main themes.

First, in terms of the number of published papers, and according to the changes over time and in the number of publications, international cultural heritage tourism research from 2002 to 2022 falls into three stages: a slow growth stage (2002–2007), a stable growth stage (2008–2016), and a rapid growth stage (2017–2022). The overall trend is upward. This trend also indirectly proves the reliability of Zhang and Xu et al. 's views that cultural heritage tourism, as a typical practice of cultural and tourism integration, has attracted wide attention in recent years [109, 110].

Second, in terms of cooperation analysis, there are several main researchers in cultural heritage tourism research; Zhang Mu [43], Timothy J Lee [111], LI XI [112], Jose Alvarez-Garcia [113], and Rob Law [7] have played an important role in research on international cultural heritage tourism, although no core network has yet formed. At the level of issuing institutions, a network of research institutions on cultural heritage tourism can be identified. These include Hong Kong Polytech University, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Jinan University, Sun Yat Sen University, and City University Macau, although no core research network has yet been formed. At the national level, research on cultural heritage tourism has attracted the attention of scholars from all over the world. China, Spain, Italy, the United States, and the United Kingdom have played an important role in the development of cultural heritage tourism research. Although Chinese scholars have published the largest number of papers in the world, their centrality is low. The centrality of Italian scholars, who have published the third-largest number of papers, ranks first in the world. This finding shows indirectly that Chinese scholars in the field of cultural heritage tourism should strengthen their international cooperation and improve their international influence [30].

Third, in terms of co-citation analysis, since 2002, papers of UNESCO have been cited 129 times, and papers by E Cohen have been cited 90 times. Annals of Tourism Research is the most cited journal, with 441 citations and impact factors of 5.493, 5.908, and 9.011 for the years 2018–2020, respectively. Tourism Management, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Sustainability, and Journal of Travel Research follow, with 433, 202, 191, and 169 citations respectively. The Research results indirectly indicate that the authors such as UNESCO and journals such as Annals of Tourism Research have made important contributions to the study of rich cultural heritage tourism.

Fourth, in terms of research hotspots, as with most research hotspots, the evolution of cultural heritage tourism research is mainly influenced by politics, culture, ecology and technology. However, this study argues that the question of how to achieve sustainable development has been the central concern of cultural heritage tourism in the past, which can be attributed to the non-renewable nature of cultural heritage. Furthermore, this research result further supports the notion that achieving sustainable development goals is an essential task in tourism studies [114]. It requires striking a balance between the economic, environmental, and social needs of all stakeholders involved [115]. In addition, the consumer behavior of cultural heritage tourism is an issue that needs to be further explored in the context of interdisciplinary integration [116]. Whether it is possible for heritage residents [24] or tourists [117] to accept the development and utilization of cultural heritage, and whether they can preserve local culture through cultural heritage tourism experience is an area that needs further in-depth research. A finding that is perhaps surprising is that tourist satisfaction is at the forefront of cultural heritage tourism research [92]. One explanation is that with improvements in living standards, demand for cultural heritage tourism has gradually increased, which requires corresponding improvements in the provision of quality services within cultural heritage tourism. This echoes the conclusions of Atsbha et al. that heritage tourism should provide a reasonable level of visitor satisfaction and must ensure that it provides them with an important experience [53]. At the same time, this study finds that rural development [95], cultural heritage management [100], and stakeholders [102] are receiving more and more attention from scholars in the field of cultural heritage tourism. In particular, the countryside has a large amount of cultural heritage [118]. One focus of current research is how to realize the rational distribution of stakeholders’ resources through effective management methods that take into account the economic, social, cultural, and ecological value of cultural heritage to rural development [97]. China has more than 5,000 years of history and world-renowned cultural heritage [119]. How to combine China's economic development with cultural heritage protection is also the mainstream issue of current research [87]. Another research trend concerns museum tourism and science and technology tourism as new forms of cultural heritage tourism, which indicates that cultural heritage tourism has transformed from traditional tourism to in-depth tourism. At present, with the rapid progress of science and technology, the rise of virtual tourism will open new ideas for cultural heritage tourism [120]. How to improve tourist satisfaction in cultural heritage tourism is an important new trend in global cultural heritage tourism research; this study suggests that promoting museum tourism and technology tourism can give tourists a better tourism experience, thereby improving consumer satisfaction.

Conclusion

This study provides cultural heritage tourism researchers with a quantitative, bibliometric review of the cultural heritage tourism literature. The results offer a deeper understanding of the development and evolution of the global cultural heritage tourism field from 2002 to 2022. The conclusions are basically consistent with those of other scholars in this field. However, the novelty of this study is threefold: the finding that China is a research object with great research potential and research value; the identification of the deep integration of cultural heritage tourism and technology, as well as cultural heritage tourism and museums, as the main trend in the development of cultural heritage tourism development; and the clarification that consumer behavior will remain the focus of research in the field of cultural heritage tourism for a long time to come. This raises the question of how to enhance the identity and perceived value of heritage residents and tourists by improving the authenticity and sustainability of cultural heritage tourism. The answers lie in providing consumers with satisfying travel experiences, thereby guiding heritage tourism toward a balance of consumption and the protection of the heritage and heritage residents.

This is the first English-language study to analyze cultural heritage tourism systematically and comprehensively using the SSCI database and bibliometric analysis methods. The results provide insights into cultural heritage tourism, giving researchers valuable information and new perspectives on potential collaborators, hotspots, and future research directions. In addition, by emphasizing the importance of cultural heritage tourism as an issue of concern around the world, it provides a more comprehensive perspective from which scholars from all over the world can conduct research into cultural heritage tourism. Its findings can be used as a reference on an international scale, especially in developing countries with rich cultural heritage resources and large populations.

However, this study has some limitations that should be noted. Because the data are taken from the SSCI database, the results apply only to humanities and social sciences research and cannot be generalized to other disciplines, especially science, engineering, and ecology. Different disciplines have their own databases, and it is therefore recommended that further research be conducted to compare and analyze results across disciplines.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

UNESCO. UNESCO convention for the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. Int Leg Mater. 1972;11(6):1358–66.

Russo AP. The “vicious circle” of tourism development in heritage cities. Ann Tourism Res. 2002;29(1):28–48.

Lee S, Phau I, Hughes M, Li YF, Quintal V. Heritage tourism in Singapore Chinatown: a perceived value approach to authenticity and satisfaction. J Travel Tour Mark. 2016;33(7):981–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1075459.

Ji F, Wang F, Wu B. How does virtual tourism involvement impact the social education effect of cultural heritage? J Destin Mark Manage. 2023;28:100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2023.100779.

Edwards JR. The UK heritage coasts: an assessment of the ecological impacts of tourism. Ann Tourism Res. 1987;14(1):71–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(87)90048-X.

Poria Y, Butler R, Airey D. The core of heritage tourism. Ann Tourism Res. 2003;30(1):238–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00064-6.

Lan TN, Zheng ZY, Tian D, Zhang R, Law R, Zhang M. Resident-tourist value co-creation in the intangible cultural heritage tourism context: the role of residents’ perception of tourism development and emotional solidarity. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(3):1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031369.

Gu YQ. Evaluation of agricultural cultural heritage tourism resources based on grounded theory on example of ancient Torreya grandis in Kuaiji mountain. J Environ Prot Ecol. 2018;19(3):1193–9.

Gonzalez-Rodriguez MR, Diaz-Fernandez MC, Pino-Mejias MA. The impact of virtual reality technology on tourists’ experience: a textual data analysis. Soft Comput. 2020;24(18):13879–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-020-04883-y.

Rasoolimanesh SM, Seyfi S, Rather RA, Hall CM. Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tour Rev. 2022;77(2):687–709. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2021-0086.

Aas C, Ladkin A, Fletcher J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann Tourism Res. 2005;32(1):28–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.005.

Ruiz Ballesteros E, Hernández RM. Identity and community—reflections on the development of mining heritage tourism in Southern Spain. Tour Manage. 2007;28(3):677–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.001.

Yang C, Liu T. Social media data in urban design and landscape research: a comprehensive literature review. Land. 2022;11(10):1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101796.

Guo Y, Xu Z, Cai M, Gong W, Shen C. Epilepsy with suicide: a bibliometrics study and visualization analysis via citespace. Front Neurol. 2022;12:823474. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.823474.

Chen C. CiteSpace: a practical guide for mapping scientific literature. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2016.

Guan H, Huang T, Guo X. Knowledge mapping of tourist experience research: based on citespace analysis. SAGE Open. 2023;13(2):21582440231166844.

Su X, Li X, Kang Y. A bibliometric analysis of research on intangible cultural heritage using citespace. SAGE Open. 2019;9(2):2158244019840119. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019840119.

Yang S, Zhang L, Wang L. Key factors of sustainable development of organization: bibliometric analysis of organizational citizenship behavior. Sustainability. 2023;15(10):8261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108261.

Zhang CX, Yang ZP. Coordinated development of cultural heritage protection and tourism development—take xinjiang as an example. Agro Food Industry Hi Tech. 2017;28(1):2851–4.

Dai TC, Zheng X, Yan J. Contradictory or aligned? The nexus between authenticity in heritage conservation and heritage tourism, and its impact on satisfaction. Habitat Int. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102307.

Su R, Bramwell B, Whalley PA. Cultural political economy and urban heritage tourism. Ann Tourism Res. 2018;68:30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.11.004.

Timothy DJ. Tourism and the personal heritage experience. Ann Tourism Res. 1997;24(3):751–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00006-6.

Gannon M, Rasoolimanesh SM, Taheri B. Assessing the mediating role of residents’ perceptions toward tourism development. J Travel Res. 2021;60(1):149–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519890926.

Tian D, Wang QY, Law R, Zhang M. Influence of cultural identity on tourists’ authenticity perception, tourist satisfaction, and traveler loyalty. Sustainability-Basel. 2020;12(16):6344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166344.

Jaafar M, Noor SM, Rasoolimanesh SM. Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: a case study of the lenggong world cultural heritage site. Tour Manage. 2015;48:154–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.018.

Errichiello L, Micera R, Atzeni M, Del Chiappa G. Exploring the implications of wearable virtual reality technology for museum visitors’ experience: a cluster analysis. Int J Tour Res. 2019;21(5):590–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2283.

Ferretti V, Gandino E. Co-designing the solution space for rural regeneration in a new World Heritage site: a choice experiments approach. Eur J Oper Res. 2018;268(3):1077–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.10.003.

Szromek AR, Herman K, Naramski M. Sustainable development of industrial heritage tourism—a case study of the industrial monuments route in Poland. Tour Manage. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104252.

Arnaboldi M, Spiller N. Actor-network theory and stakeholder collaboration: the case of cultural districts. Tour Manage. 2011;32(3):641–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.016.

Olya HG, Shahmirzdi EK, Alipour H. Pro-tourism and anti-tourism community groups at a world heritage site in Turkey. Curr Issues Tour. 2019;22(7):763–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1329281.

Gonzalez J, Alonso DO. Sustainable development goals in the Andalusian olive oil cooperative sector: heritage, innovation, gender perspective and sustainability. New Medit. 2022;21(2):31–42. https://doi.org/10.30682/nm2202c.

Russo AP. The “vicious circle” of tourism development in heritage cities. Ann Tourism Res. 2002;29(1):165–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00029-9.

van der Borg J, Costa P, Gotti G. Tourism in European heritage cities. Ann Tourism Res. 1996;23(2):306–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00065-8.

Edwards JA, Coit JCL. Mines and quarries: industrial heritage tourism. Ann Tourism Res. 1996;23(2):341–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00067-4.

Russo AP, van der Borg J. Planning considerations for cultural tourism: a case study of four European cities. Tour Manage. 2002;23(6):631–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00027-4.

Chen C. Mapping scientific frontiers: the quest for knowledge visualization. J Doc. 2003;59(3):364.

Chen CM. CiteSpace II: detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol. 2006;57(3):359–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317.

Li X, Li H. A visual analysis of research on information security risk by using citespace. Ieee Access. 2018;6:63243–57. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2873696.

Katz JS, Martin BR. What is research collaboration? Res Policy. 1997;26(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(96)00917-1.

Henry S. Co-citation in the scientific literature: a new measure of the relationship between two documents. J Am Soc Inform Sci. 1973;24(4):265–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630240406.

Ondimu KI. Cultural tourism in Kenya. Ann Tourism Res. 2002;29(4):1036–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00024-5.

Price DJ, Monaghan JJ. An energy-conserving formalism for adaptive gravitational force softening in SPH and N-body codes. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 2006;374(4):1347–58.

Qiu QH, Zhang M. Using content analysis to probe the cognitive image of intangible cultural heritage tourism: an exploration of Chinese social media. Isprs Int J Geo-Inf. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10040240.

Yao D, Zhang K, Wang L, Law R, Zhang M. From religious belief to intangible cultural heritage tourism: a case study of Mazu belief. Sustainability-Basel. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104229.

Yang J, Luo JM, Lai I. Construction of leisure consumer loyalty from cultural identity-a case of Cantonese opera. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(4):1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041980.

Zhang GG, Chen XY, Law R, Zhang M. Sustainability of heritage tourism: a structural perspective from cultural identity and consumption intention. Sustainability-Basel. 2020;12(21):9199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219199.

Song HQ, Chen PW, Zhang YX, Chen YC. Study progress of important agricultural heritage systems (IAHS): a literature analysis. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(19):10859. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910859.

Freeman LC. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc Netw. 1978;3(1):215–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7.

Chen C, Dubin R, Kim MC. Emerging trends and new developments in regenerative medicine: a scientometric update (2000–2014). Expert Opin Biol Th. 2014;14(9):1295.

Adabre MA, Chan A, Darko A. A scientometric analysis of the housing affordability literature. J Hous Built Environ. 2021;36(4):1501–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09825-0.

Dang Q, Luo ZM, Ouyang CH, Wang L, Xie M. Intangible cultural heritage in china: a visual analysis of research hotspots, frontiers, and trends using citespace. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(17):9865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179865.

Kolar T, Zabkar V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: an oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour Manage. 2010;31(5):652–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.010.

Apostolakis A. The convergence process in heritage tourism. Ann Tour Res. 2003;30(4):795–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00057-4.

Yeoman I, Brass D, Mcmahon-Beattie U. Current issue in tourism: the authentic tourist. Tour Manage. 2007;28(4):1128–38.

Song J. Cultural production and productive safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage. Cult Herit. 2012;1:5–157.

Farrelly F, Kock F, Josiassen A. Cultural heritage authenticity: a producer view. Ann Tourism Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102770.

Su JJ. Conceptualising the subjective authenticity of intangible cultural heritage. Int J Herit Stud. 2018;24(9):919–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1428662.

Zhang Y, Lee TJ. Alienation and authenticity in intangible cultural heritage tourism production. Int J Tour Res. 2022;24(1):18–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2478.

Shen SY, Guo JY, Wu YY. Investigating the structural relationships among authenticity, loyalty, involvement, and attitude toward world cultural heritage sites: an empirical study of Nanjing Xiaoling tomb. China Asia Pac J Tour Res. 2014;19(1):103–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2012.734522.

Su JJ. A difficult integration of authenticity and intangible cultural heritage? The case of Yunnan, China. China Perspect. 2021;3:29–39.

Dominguez-Quintero AM, Gonzalez-Rodriguez MR, Paddison B. The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Curr Issues Tour. 2020;23(2):248–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1502261.

Su X, Li X, Chen W, Zeng T. Subjective vitality, authenticity experience, and intangible cultural heritage tourism: an empirical study of the puppet show. J Travel Tour Mark. 2020;37(2):258–71.

Naqvi M, Jiang YS, Naqvi MH, Miao M, Liang CY, Mehmood S. The effect of cultural heritage tourism on tourist word of mouth: the case of Lok Versa Festival, Pakistan. Sustainability-Basel. 2018;10(7):2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072391.

Theodossopoulos D. Laying claim to authenticity: five anthropological dilemmas. Anthropol Quart. 2013;86(2):337–60. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2013.0032.

Jones S, Yarrow T. Crafting authenticity: an ethnography of conservation practice. J Mat Cult. 2013;18(1):3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183512474383.

Jones S, Jeffrey S, Maxwell M, Hale A, Jones C. 3D heritage visualisation and the negotiation of authenticity: the ACCORD project. Int J Herit Stud. 2018;24(4):333–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1378905.

Kastenholz E, Eusebio C, Carneiro MJ. Segmenting the rural tourist market by sustainable travel behaviour: insights from village visitors in Portugal. J Destin Mark Manage. 2018;10:132–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.09.001.

Jeon MM, Kang M, Desmarais E. Residents’ perceived quality of life in a cultural-heritage tourism destination. Appl Res Qual Life. 2016;11(1):105–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9357-8.

Shen SY, Schuttemeyer A, Braun B. Visitors’ intention to visit world cultural heritage sites: an empirical study of Suzhou, China. J Travel Tour Mark. 2009;26(7):722–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400903284610.

Li XY. Advantages and Countermeasures of the Development of China's Food Tourism Industry. In X Chu (Ed.) proceedings of the 2017 4th international conference on education, management and computing technology (ICEMCT 2017). 4th International Conference on Education, Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT). 2017; 101: pp. 1118–1122.

Guisande AM. Urban impact of cultural tourism. In R Amoeda, S Lira, C Pinheiro (Eds.), Heritage 2010: heritage and sustainable development, VOLS 1 AND 2. 2nd International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development. 2010; 1061–1069.

Snowball JD, Courtney S. Cultural heritage routes in South Africa: effective tools for heritage conservation and local economic development? Dev So Afr. 2010;27(4):563–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2010.508589.

Al-Hagla KS. Sustainable urban development in historical areas using the tourist trail approach: a case study of the cultural heritage and urban development (CHUD) project in Saida, Lebanon. Cities. 2010;27(4):234–48.

Nocca F. The role of cultural heritage in sustainable development: multidimensional indicators as decision-making tool. Sustainability-Basel. 2017;9(10):1882. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101882.

Trovato MG, Ali D, Nicolas J, El Halabi A, Meouche S. Landscape risk assessment model and decision support system for the protection of the natural and cultural heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean area. Land. 2017;6(4):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6040076.

Nobre H, Sousa A. Cultural heritage and nation branding—multi stakeholder perspectives from Portugal. J Tour Cult Change. 2022;20(5):699–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2021.2025383.

Carnegie E, Mccabe S. Re-enactment events and tourism: meaning, authenticity and identity. Curr Issues Tour. 2008;11(4):349–68. https://doi.org/10.2167/cit0323.0.

Tian D, Wang Q, Law R, Zhang M. Influence of cultural identity on tourists’ authenticity perception, tourist satisfaction, and traveler loyalty. Sustainability-Basel. 2020;12(16):6344.

Zhang J, Tang WY, Shi CY, Liu ZH, Wang X. Chinese calligraphy and tourism: from cultural heritage to landscape symbol and media of the tourism industry. Curr Issues Tour. 2008;11(6):529–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802475836.

Crang M. Travelling ethics: valuing harmony, habitat and heritage while consuming people and places. Geoforum. 2015;67:194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.06.010.

Wang RL, Liu G, Zhou JY, Wang JH. Identifying the critical stakeholders for the sustainable development of architectural heritage of tourism: from the perspective of China. Sustainability-Basel. 2019;11(6):1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061671.

Yan H, Bramwell B. Cultural tourism, ceremony and the state in China. Ann Tourism Res. 2008;35(4):969–89.

Giliberto F, Labadi S. Harnessing cultural heritage for sustainable development: an analysis of three internationally funded projects in MENA Countries. Int J Herit Stud. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1950026.

Daugstad K, Rønningen K, et al. Agriculture as an upholder of cultural heritage? Conceptualizations and value judgements—A Norwegian perspective in international context. J Rural Stud. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.06.002.

Chirikure S, Pwiti G. Community involvement in archaeology and cultural heritage management—an assessment from case studies in southern Africa and elsewhere. Curr Anthropol. 2008;49(3):467–85. https://doi.org/10.1086/588496.

Mcgill D. The public’s archaeology: utilizing ethnographic methods to link public education with accountability in archaeological practice. J World Archaeol Congr. 2010;6(3):468–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-010-9151-7.

Gheyle W, Dossche R, Bourgeois J, Stichelbaut B, Van Eetvelde V. Integrating archaeology and landscape analysis for the cultural heritage management of a world war I Militarised landscape: the German field defences in Antwerp. Landsc Res. 2014;39(5):502–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2012.754854.

Chung N, Lee H, Kim JY, Koo C. The role of augmented reality for experience-influenced environments: the case of cultural heritage tourism in Korea. J Travel Res. 2018;57(5):627–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517708255.

Verma A, Rajendran G. The effect of historical nostalgia on tourists’ destination loyalty intention: an empirical study of the world cultural heritage site—Mahabalipuram, India. Asia Pac J Tour Res. 2017;22(9):977–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1357639.

Dieck M, Jung TH. Value of augmented reality at cultural heritage sites: a stakeholder approach. J Destin Mark Manage. 2017;6(2):110–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.03.002.

Buonincontri P, Marasco A, Ramkissoon H. Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: a conceptual framework. Sustainability-Basel. 2017;9(7):1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071112.

Taheri B, Gannon MJ, Kesgin M. Visitors’ perceived trust in sincere, authentic, and memorable heritage experiences. Serv Ind J. 2020;40(9–10):705–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1642877.

Zhang TH, Yin P, Peng YX. Effect of commercialization on tourists’ perceived authenticity and satisfaction in the cultural heritage tourism context: case study of Langzhong Ancient city. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(12):6847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126847.

Jebbouri A, Zhang HQ, Wang L, Bouchiba N. Exploring the relationship of image formation on tourist satisfaction and loyalty: evidence from China. Front Psychol. 2021;12:748534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.748534.

de Luca C, Lopez-Murcia J, Conticelli E, Santangelo A, Perello M, Tondelli S. Participatory process for regenerating rural areas through heritage-led plans: the RURITAGE community-based methodology. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(9):5212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095212.

Egusquiza A, Zubiaga M, Gandini A, de Luca C, Tondelli S. Systemic innovation areas for heritage-led rural regeneration: a multilevel repository of best practices. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(9):5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095069.

Sardaro R, La Sala P, De Pascale G, Faccilongo N. The conservation of cultural heritage in rural areas: stakeholder preferences regarding historical rural buildings in Apulia, southern Italy. Land Use Policy. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lusepol.2021.105662.

Rautio S. Material compromises in the planning of a ‘traditional village’ in Southwest China. Soc Anal. 2021;65(3):67–87. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2021.6503OF2.

Dans EP, Gonzalez PA. Sustainable tourism and social value at World Heritage Sites: towards a conservation plan for Altamira, Spain. Ann Tourism Res. 2019;74:68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.10.011.

Carbone F, Oosterbeek L, Costa C, Ferreira AM. Extending and adapting the concept of quality management for museums and cultural heritage attractions: a comparative study of southern European cultural heritage managers’ perceptions. Tour Manag Perspect. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100698.

Manyane RM. Rethinking trans-boundary tourism resources at the Botswana-North West Province border. S Afr Geogr J. 2017;99(2):134–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2016.1208579.